_________________________________

Walt Disney's Nine Old Men: The Flipbooks

_________________________________

Open this box and discover a world of Disney animation that's never been seen before! The nine hardcover flipbooks contained within the box pay tribute to Walt Disney's original animators—the Nine Old Men: Les Clark (1907—1979), Eric Larson (1905—1988), Frank Thomas (1912—2004), John Lounsbery (1911—1976), Ward Kimball (1914—2002), Ollie Johnston (1912—2008), Marc Davis (1913—2000), Wolfgang "Woolie" Reitherman (1909—1985), and Milt Kahl (1909—1987). These artists were the geniuses behind such classic Disney films as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Bambi, Fantasia, Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, and Peter Pan.

Edited by Academy Award®-winning director Pete Docter, each flipbook features a scene from an animated Disney feature in its original line-drawn form, having been selected from among a wide range of films for great movement and classic characters. Such iconic clips from the reel of Disney animation history include: Lady and the Tramp's moonlit spaghetti dinner; Sorcerer Mickey's ordeal with a horde of mops in Fantasia; and Thumper's announcement in Bambi that a prince has been born!

In addition to the flipbooks, the box contains a booklet detailing the incredible talents that the Nine Old Men contributed to The Walt Disney Animation Studios, for which they have all been named Disney Legends. With their enduring appeal, precise timing, and focused staging, it's no wonder that the films created by these animation pioneers have been enjoyed by generation after generation.

_________________________________

The Nine Old Men – Pete Docter (1968-)

_________________________________

I LOVE FLIPBOOKS. In today's age, where it takes a computer to unlock a door, you can bring characters to life with nothing but paper in your hands.

"Flipping" is how animators check their work before shooting it on film. Although the drawings in this boxed set were intended to be inked, painted, and projected on the big screen, you are seeing them much as the original animators first saw them.

The "Nine Old Men" was the name Walt Disney jokingly gave his then middle-aged animators, a reference to President Franklin D. Roosevelt's moniker for the Supreme Court justices. Though there were certainly other talented artists at the Studio (and hopefully someday there'll be flip books featuring their work as well), these nine were among the top innovators in the field. They also acted as a peer review board, advising and guiding other animators at the Studio, making the nickname even more fitting.

Animators at "Disney's"* saw themselves as "actors with pencils." They were truly the stars of the Studio, and were treated as such. Though their own likenesses didn't appear on film—except as caricatures—their acting sensibilities did. And an actor couldn't ask for a broader range of roles. As Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston wrote in The Illusion of Life, "What other actor could believably assume the role of dog, mouse, or little girl?"

As these artists discovered, animation is about motion; no single drawing was designed to be experienced on its own. It is only when the drawings are flipped that they come to life. Flipped together, movement seen in no individual drawing appears mysteriously, as if from nowhere. I hope you are as amazed by this mystery as I am.

The scenes selected here represent the pinnacle of Disney animation throughout its golden age. The drawings in these books are arranged back to front. As the animators discovered, this makes it much easier to see the images on the pages.

Enjoy!

_________________________________

Les Clark (1907–1979)

_________________________________

_________________________________

Les Clark, the first of Disney's "Nine Old Men," was born in Ogden, Utah, in 1907. His family moved to Los Angeles, where he attended Venice High School. While working a summer job near the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio, Les got up the courage to ask Walt for a job. His drawings were favorably received, and he started in the Ink and Paint department.

Les won his first animation assignment on Disney's first Silly Symphony, The Skeleton Dance. He developed an adept hand at animating Mickey Mouse, beginning with a scene in Steamboat Willie. He animated on or directed nearly 20 features, and more than 100 shorts.

After serving as sequence director on Sleeping Beauty, Walt asked Les to direct television specials and educational films, including Donald in Mathmagic Land and Donald and the Wheel.

Les retired in 1975; he died in September 1979.

_________________________________

|

| Remembering Les – John Canemaker (1943-) |

_________________________________

When shy, part-time confectionery waiter Leslie James Clark (1907-1979) graduated from high school on a Thursday and reported to work the following Monday (February 23, 1927), his new boss, Walt Disney, warned him the job might be temporary. By the time Les Clark retired in 1975, he was a senior animator and director, and the longest continuously employed member of Walt Disney Productions.

I met Clark in July 1973, two years before he retired at age 68, during my first visit to the Disney Studio. I found him to be reserved, quiet, and, yes, shy. Yet he gave me an interview so full of information that I used much of it almost three decades later in my book Walt Disney's Nine Old Men and the Art of Animation.

That was one of the remarkable things about Les Clark his mild-mannered, reticent, apparently ego-free qualities belied his tremendous gifts as a masterly animator of surpassing skill. Everything he drew came alive with charm and personality.

He entered animation at a crucial time during the silent era—a year before Mickey Mouse's "birth"—and participated in events that shaped not only Disney's future, but also the art form of character animation itself. At first, Clark was apprentice to sorcerer/legendary animator Ub Iwerks, whom Clark fondly remembered as a "very gifted" and very patient" teacher.

Clark emulated his master in "rhythm animation"—smooth "ripple" actions repeated in pleasing cycles and patterns of motion in many a Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony short. Traces of this magical, cartoony animation style are in the elastic pink train sambaing to "Baia" in The Three Caballeros.

Soon the pupil surpassed his mentor. Diligently working on his draftsmanship skills throughout his career, Clark became a first-rate character animation "actor," specializing in Mickey Mouse. It was Les Clark who animated dynamic personality scenes in The Band Concert and Fantasia, both among the mouse's greatest acting performances.

What was also amazing about Clark was his versatility as an animator. He "played" everything from a buxom operatic hen (Clara Cluck) to a delicate dewdrop fairy to an inebriated country bumpkin of a rodent (The Country Cousin) to a frustrated bee trapped in a surreal landscape (Bumble Boogie); Clark's animation ranged from gigantic Paul Bunyan to tiny Jiminy Cricket and Tinker Bell on TV's Mickey Mouse Club.

Often, Clark was handed technically difficult assignments, which he accepted with good humor and managed with seriousness of purpose and consummate skill. One such assignment was Snow White dancing with dwarfs, a sequence of subtle changes in perspective as the characters cavort; another was the combining of a live actor with animated animals in the joyous "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah'" musical number from Song of the South.

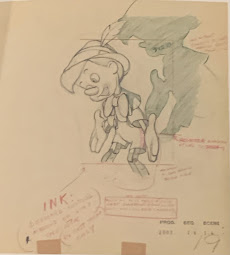

Clark's animation provided the necessary emotional mortar to hold scenes together in many films, including Pinocchio and Alice in Wonderland. Art Babbitt, another great animator and a tough critic, always spoke admiringly of Clark, who "never received the recognition the others [animators] did. And he should have, Babbitt said, "because he was marvelous! Terrific animator, very inventive. But taken for granted."

Les Clark's development from a "rubber-hose-and-circle" patternmaker into a master personality animator matches the best of his peers. His work through the years deserves careful study, and today's DVDs—and this flipbook offer the ambitious student an opportunity to learn from one of the greats.

_________________________________

Wolfgang Reitherman (1909–1985)

_________________________________

_________________________________

Born in Munich, Germany, on June 26, 1909, Wolfgang "Woolie" Reitherman came to the U.S. as an infant and was raised in Sierra Madre, California. Intending to become an aircraft engineer, he attended Pasadena Junior College and took a job at Douglas Aircraft. In 1931 he enrolled at Chouinard Art Institute to study watercolor. Through connections there, he discovered animation and joined The Walt Disney Studios in 1933.

Woolie animated on more than 30 shorts and many features, becoming especially valued for his skill with action and comedy. During World War Il he left the Studio to briefly serve as an ace pilot.

Woolie became the first animator to direct an entire animated feature, beginning with The Sword in the Stone in 1963. After nearly 50 years with the Studio, Woolie retired in 1981, and died on May 22, 1985, in Burbank, California.

_________________________________

|

| Remembering Woolie – Don Hahn (1955-) |

_________________________________

Wolfgang "Woolie" Reitherman was a man's man. Perpetually clad in a Hawaiian shirt, he reeked of the confidence that came from his years as an ace pilot during World War II, where he flew in Africa, India, China, and the South Pacific and earned a Distinguished Flying Cross medal.

Woolie joined Disney in 1933. His animation—the dinosaur battle in Fantasia, Monstro the whale in Pinocchio, and the clash between Prince Phillip and the dragon in Sleeping Beauty—mirrored the way he lived his life: powerful and full of vitality, energy, and quality.

He soon emerged as a natural leader, so much so that Walt Disney left him the keys to the Animation department in the mid-1960s as Disney's attentions turned to Disneyland, television, and live-action films. After Walt's death in 1966, Woolie became the galvanizing force of the animation crew during a very unsettling time.

I worked closely with him as an assistant director. The day I met him, he shook my hand with a grip that dislodged my ring finger. If John Wayne and Robert Mitchum had a baby, it would have been Woolie. When he talked, he had the habit of chomping on an unlit cigar until the end was horribly soggy, whereupon he would reach into his drawer, pull out a stained pair of scissors, cut off the end, and continue chomping away, all without missing a word.

He talked about flying a Grumman F6F Hellcat on a bombing run. I talked about my new Volkswagen Beetle. We compared favorite movies. His was The Guns of Navarone, mine was Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

I got the job, but I knew this guy would forever influence my life. Woolie was not a fanboy animator, nor a cartoonist; he was a filmmaker who drew deeply from his life experience. He was a creative producer like Walt Disney, and I knew I wanted to be just like him someday.

_________________________________

Eric Larson (1905–1988)

_________________________________

_________________________________

Born in Cleveland, Utah, in 1905, Eric avidly read comic-humor magazines such as Punch and Judge. He majored in journalism at the University of Utah, where he won a reputation for being a creative humorist and cartoonist. After graduating, Eric traveled around America freelancing for various magazines. In 1933, taking the advice of a friend, Eric submitted some of his sketches to The Walt Disney Studios and was hired as an assistant animator.

Eric worked as an animator on such feature films as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Fantasia, Bambi, Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty, and The Jungle Book, as well as nearly 20 shorts and six television specials. Later, he expanded the Studios Talent Program to find and train new and talented animators, acting as a mentor to many.

Eric retired in 1986 and died on October 25, 1988, in La Canada-Flintridge, California.

_________________________________

|

| Remembering Eric – John Musker (1953-) |

_________________________________

A gifted animator and a natural teacher with a soft spot for young people trying to learn the craft, Eric Larson had been placed by Studio management in charge of their new in-house talent development program. It was there that, with great patience, clarity, and warmth, he essentially taught me and many others—people like Glen Keane and Ron Clements, for example—how to animate. He himself was mentored by Ham Luske, one of the principal animators at Disney in the thirties, and later its primary director, Ham's lessons of sincerity, action analysis, and caricature were deeply imprinted on Eric, who passed them on, along with countless other things he had learned from artists like Freddie Moore and Bill Tytla, not to mention Walt himself, to wide-eyed trainees like me.

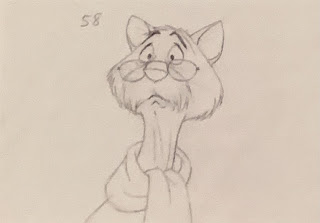

Eric had an understated touch to his own animation. He found the essential truth, warmth, and sincerity of whatever character he animated. He gave us a Figaro in Pinocchio, full of gentle humor, and well-observed traits, both of a real kitten and an inquisitive and occasionally exasperated child. The grandfatherly curmudgeon owl in Bambi was his. He animated the loopy Aracuan bird who motored along the frame's edge in The Three Caballeros, and Sasha, the Russian-hatted bird in Peter and the Wolf, who, like many of Eric's characters, steals the show without trying to. But where this genteel and gentlemanly Mormon came up with Peg, the saucy show dog in Lady and the Tramp, I'll never know, although I can personally attest that Eric's courtly manner and twinkling blue eyes had legions of young, pretty female admirers from the ranks of the new trainees.

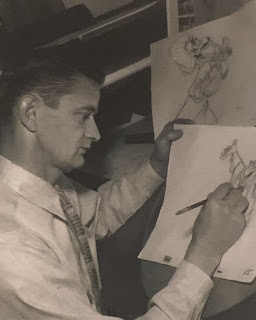

While in the training program, I would bring Eric a "scene" of my animation. From my haphazard stack of drawings, he would pull out the "keys," the crucial poses. He would put a sheet of fresh paper over them on the disk, and holding his pencil counterbalanced by his extended pinkie riding along the paper (a pinkie calloused from years of animation—a callous, he said all good animators had), Eric would draw far more powerful, clear, and carefully analyzed versions of what I had done. These drawings were often diagrams, which did not necessarily look like my character. But the silhouettes, arcs, paths of action, the clear "anticipations," and the ideas on timing, all honed from his years on the board, were magically transformative. Poses now related to one another in a fluid and dynamic way. Actions were clearer. Thought processes were communicated. "Positive statements" was his mantra.

Eric's words to me then still ring in my ears now, some 35 years later. He also said. "Our only limit in animation is our own imaginations, and our ability to draw what we imagine." I try and live my animation life by those words that came from the always supportive, gentle, powerful mentor with the high-waisted pants and the sparkling blue eyes: Eric Larson. I owe him everything.

_________________________________

Milt Kahl (1909–1987)

_________________________________

_________________________________

Milt Kahl was born in San Francisco in 1909. He cut short his high school education to pursue his dream of becoming a magazine illustrator or cartoonist. He worked on retouching photos and pasting up layouts at several San Francisco Bay Area newspapers. Struggling with his own commercial art business during the Great Depression, Milt saw the Disney short "Three Little Pigs" and applied for work at the Studio in June 1934. He started as an assistant animator.

Milt rose to become one of the world's best animators in the world. His extraordinary draftsmanship often landed him technically challenging assignments, such as Peter Pan, Alice of Alice in Wonderland, and the Prince in Sleeping Beauty. Yet he was equally at home animating comedic or animal characters like Shere Khan or Tramp.

Milt's marvelous sense of design made him a leading contributor to many Disney characters for years.

After nearly 40 years with Disney, Milt retired from the Studio in 1976. He died on April 19, 1987.

_________________________________

|

| Remembering Milt – Andreas Deja (1957-) |

_________________________________

As an art student in the late seventies, I wrote a fan letter to Milt Kahl, complimenting him on his superb animation and characters. It took a while, but I received a response. He thanked me for my flattering remarks and informed me that he had left the field of animation and lived in retirement near San Francisco. I was shocked. Without Milt Kahl, who would design new characters and set drawing standards for future Disney films? It seemed like the end of an era.

For almost 40 years, Milt Kahl's drawings and animation had influenced and changed the style of Disney animation. The characters in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs were drawn in a round and dimensional way; by Sleeping Beauty, Milt's sense for strong graphic design helped create a new look for Disney animation.

Walt Disney was very fortunate to have Milt Kahl on his animation team. Many of the other animators would ask the master draftsman for help to improve their drawings.

This gave visual continuity to a character animated by several artists. Milt cussed and yelled in frustration as he redrew and improved a colleague's scene. "Why can't these guys draw like me?"

Once during the production of Peter Pan, in which Milt supervised the animation of the title character, Walt wasn't pleased with all the different looking Pans in the screening. Milt bluntly responded: "That's because you don't have any talent in this place!"

Of course Walt disagreed. Ollie Johnston later said that Milt was the only animator who could get away with arguing with the boss.

Milt's animation is unique. His characters always move with believable weight. His acting choices show a great sense of personality. Milt said he could animate anything well, and he was right.

Whether he drew a dancing llama, a prince, a newborn deer, or an evil tiger, his talent had no limits.

_________________________________

Ward Kimball (1914–2002)

_________________________________

_________________________________

Born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on March 4, 1914, Ward's first recognizable drawing was of a steam locomotive. Mind set on becoming a magazine illustrator, he enrolled at the Santa Barbara School of Art in California. While there he happened to catch Walt Disney's "Three Little Pigs" at a local matinee, and with portfolio in hand, Ward headed for Hollywood, joining The Walt Disney Studios in 1934.

Besides animating, Ward directed several short films, produced and directed three one-hour space films for the Disneyland television show, consulted on theme park projects, was the trombone player and founder of the internationally known Dixieland jazz band Firehouse Five Plus Two, and operated a full-size locomotive in his backyard, helping to spark Walt's own interest in trains.

After nearly 40 years with the company, Ward retired in 1972 to travel with his wife, Betty. He died on July 8, 2002, in Los Angeles.

_________________________________

|

| Remembering Ward – Eric Goldberg (1955-) |

_________________________________

Ward Kimball certainly the most whacked-out member of Disney's Nine Old Men, was the studio maverick. Ward would try anything, and even though that was frequently interpreted as "anything-for-a-laugh," this quality extended far beyond the mere joke. He could do the warm, sympathetic stuff (like Jiminy Cricket), as well as the crazy, inspired lunacy (Panchito's gun barrel mouthing some of his lyrics in The Three Caballeros title song) that would become his trademark. Ward also experimented with limited animation and modern design, UPA-style, in films like Melody and Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom (an Academy Award winner). The bottom line is that Ward's work always had ideas behind it—planned insanity, if you will.

Ward's animation shared a unique quality with that of his close friend Freddie Moore—sheer boldness. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than in the piece selected for this flipbook. From Alice in Wonderland, Tweedledee and Tweedledum bounce and cavort outlandishly in a scene that looks great when you see it at speed, but reveals its true audaciousness when you look at it frame by frame. They squish like water balloons, flatten out like pancakes, poke each other, and do all manner of facial contortions and rubber-legged gavottes, leaving the viewer with this distinct thought: I can't believe he got away with that. In a nutshell (not a bad place for Ward to be), Ward Kimball spent his entire career "getting away with it," and we are all the richer and more amused for it.

_________________________________

Frank Thomas (1912–2004)

_________________________________

_________________________________

Born in Santa Monica, California, on September 5, 1912, Frank Thomas was raised in Fresno, California, where his father was president of Fresno State College. Frank's interest in drawing emerged by age nine; his interest in motion pictures developed later at Fresno State, where he wrote and directed a short film that spoofed college life. He attended Stanford University and Chouinard Art Institute, where fellow artist and rooming house boarder James Algar (a renowned Disney animator in his own right) suggested he try out as an inbetweener at the Disney Studio.

Hired in 1934, Frank's first assignment was on the short "Mickey's Elephant." He was later assigned to Snow White, and worked on most of the Disney animated classics up until his retirement in 1978.

Besides animating, Frank was also a formidable piano player in the Dixieland jazz band Firehouse Five Plus Two and wrote the definitive history textbook, Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life, with best friend Ollie Johnston.

He died on September 8, 2004.

_________________________________

|

| Remembering Frank – Ron Clements (1953-) |

_________________________________

I worked closely with Frank Thomas for around two years, starting in 1974, on the movie The Rescuers. I was a 21-year-old animation trainee, and he was my mentor. It was an unbelievably rewarding time. I felt like kind of a sorcerer's apprentice. These guys, the master Disney animators, truly were magicians. They created life, personality, entertainment out of nothing more than pencil and paper, and what a privilege to see how they did it!

Frank was thoughtful, intelligent, and articulate. He analyzed things to death and did tons of thumbnails and diagrams. He always pushed you to explore multiple options in approaching any scene before finally settling on what you felt was the very best. He was passionate, hard to please, and harder on himself than anybody. He flipped his scenes so relentlessly they were ragged, like the texture of an old treasure map. He once told me, in his whole career, he had only done a handful of scenes he was really satisfied with. He never said what they were. Pinocchio in the "I've Got No Strings" scene? Bambi on ice? Captain Hook? Certainly, I would hope, the Dwarfs tearfully mourning the death of their beloved Snow White, or the spaghetti-eating sequence in Lady and the Tramp would be among them.

Chuck Jones once called Frank the Laurence Olivier of animators, and that was accurate. He was a brilliant actor, always getting into the specific, unique thought processes of each character, pushing relationships, feelings, sincerity. The great thing is, the life he created will exist forever, to be experienced over and over again. And what could be more magical than that?

_________________________________

Ollie Johnston (1912–2008)

_________________________________

_________________________________

Oliver "Ollie" Johnston was born in Palo Alto, California, in 1912. His father was a professor of Romance languages at Stanford University, where Ollie attended as an art major. During his senior year he came to Los Angeles to study under Pruett Carter at the Chouinard Art Institute, and was approached by Disney. He joined the Studio in 1935.

Johnston's first assignment was as an inbetweener on Mickey's Garden, and a year later was promoted to apprentice animator, working under Fred Moore. His first job as a feature animator was on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. He was also one of four supervising animators on Bambi, and became a directing animator on Song of the South. He served in that capacity on nearly every one of Disney's animated classics for the next 33 years.

Ollie retired in January 1978 and went on to author three books on Disney animation, including Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life, written with lifelong friend Frank Thomas. He died on April 14, 2008.

_________________________________

|

| Remembering Ollie – Glen Keane (1954-) |

_________________________________

It is 1975, and for over 35 years Ollie has had the corner office 1D-12 at the end of the "Hall of Kings," referring to the animation greats who share that wing with him.

I am filled with awe as I knock on his door and hear Ollie's soft, airy voice say with a blend of humility and curiosity, "Come in?"

Entering, I see Ollie dressed in his cardigan sweater, surrounded by delicate pencil studies of Penny from The Rescuers. On the wall is a photo of his pride and joy, a full-sized locomotive in the snow on his property in Julian, California.

Resting on the table behind him is a brown paper sack. He and Frank Thomas are creatures of habit and sit together each day over lunch talking about the sequences they are working on, plotting how to convince the director, "Woolie" Reitherman, to see things their way. Like inseparable brothers, they have worn a path in the floor between their offices.

Holding out a wrinkled stack of animation paper, I ask, "Ollie, can you take a look at my scene?"

Without hesitation Ollie takes my drawings, and after deftly flipping them several times so he can study the movement, he takes the top and bottom drawings and sets aside the hundred or so in-betweens and comments, "I think these two are all you need. They will be our Golden Poses."

I stand behind peering over his shoulder as the master places a clean sheet over one of my drawings and proceeds to sketch with his "Kobalt Hell" blue-colored pencil. His hand moves effortlessly as his pencil appears to just "kiss" the paper.

I watch in amazement as my stiff, rudimentary drawing of a little girl is transformed into a living, breathing being. The world and the room seem to disappear, and I can actually feel the softness of her cheeks, the intensity in her brows, the sculpted dimension of her form. She appears to be alive. "Don't draw what the character is doing he says. "Draw what the character is thinking."

This is the hallmark of all of Ollie's animation, from Thumper to Mr. Smee to Mowgli. His characters actually simmer with the spark of life.

Ollie Johnston was not only a master animator but a gifted teacher who broke down the dizzying complexities of animation into bite-size principles that even the most neophyte animator could apply.

Thirty-six years later, I still see Ollie drawing.

_________________________________

Marc Davis (1913–2000)

_________________________________

To see Tinker Bell's scene in CGI, click

here.

_________________________________

An only child of Harry and Mildred Davis, Marc was born on March 30, 1913, in Bakersfield, California. His father worked in oil field developments, and the family moved wherever a new boom emerged. As a result, Marc attended more than 20 different schools across the country.

Marc joined Disney in 1935 as an apprentice animator on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and moved on to story sketch and character design on Bambi and Victory Through Air Power.

Over the years, he animated on such Disney classic features as Song of the South, Cinderella, and Alice in Wonderland, as well as many shorts.

He later became one of the original Imagineers, designing concepts and characters for many of Disneyland's premier attractions. Throughout his career, Marc was also famed for his anatomy and drawing classes at Chouinard Art Institute.

Marc died on January 12, 2000.

_________________________________

|

| Remembering Marc – Bob Kurtz |

_________________________________

How do you write about greatness? Where do I start about my dear friend and mentor, the legendary Marc Davis?

I first met Marc as a student in his Life Drawing class. I watched, fascinated, as Marc slowly twisted his cigarette into a black plastic cigarette holder. Then, through clenched teeth and cigarette pointed up at 45 degrees, Marc would reveal amazing gems of drawing wisdom. It was the best of times.

One of Marc's mantras was that good drawings and clear thinking went together, along with observation and life experience. Marc would say, "Who you are comes out in your drawings." That probably explains why Marc's animation was so versatile and full of life.

As the years passed, Marc and I grew closer. Together with Marc's talented wife and soul mate, Alice, and my wife, Theresa, we would laugh and talk into the late hours. Marc was a wonderful storyteller, and colorfully shared the experiences of his life with their many guests. Then there were those delicious late-night gourmet meals that Alice would whip up in a mere four hours. And always there would be those beloved, spoiled little dogs wandering around and about our feet.

Marc, always the thoughtful host, was also Marc the martini Zen master. With his back to you, secretly and patiently, you would see a bit of a hand move, a squeeze of this, a shake of that. No, Marc would not let you see what he was creating; it was a Houdini magic act. Each of Marc's finely crafted martinis took ten minutes to make and ten hours to recover from.

Marc and Alice's home was like a bustling railroad station; only the train whistle was missing. There was always someone about to leave, and more would drop in. There was a constant parade of affection and love. It was musical chairs without the music.

Together, Marc and Alice traveled the world, making even more friends. Every holiday season their house was filled with baskets and baskets overflowing with Christmas cards. Cards sent from around the world, maybe a thousand or more, all with warm, personal inscriptions. Marc and Alice always answered each of them personally.

Once, I brought Marc a magazine article about "Who Was the Greatest Villainess in Motion Picture History." At the top of the list, the number-one villainess was not Joan Crawford or Bette Davis; it was Cruella De Vil! Marc responded with that wonderful deep chuckle.

Beyond his prodigious talent, and in addition to being so generous with his time and encouragement to young artists, Marc was warm, open, gracious, caring, and always a gentleman. Marc was a class act.

No, Marc Davis was not a saint, but he was pretty damn close.

_________________________________

John Lounsbery (1911–1976)

_________________________________

_________________________________

John Lounsbery was born March 9, 1911, in Cincinnati, Ohio. The youngest of three sons, he was raised in Colorado, where he attended the Art Institute of Denver. He moved to Los Angeles in 1932 and worked as a freelance commercial artist while attending illustration courses at the Art Center School of Design. One of the school's instructors pointed him in the direction of The Walt Disney Studios, which was searching for artists at the time.

Starting at Disney in 1935, John specialized in "Pluto" shorts for several years before being promoted to directing animator on Dumbo, working on Timothy the mouse. Besides serving as directing animator on an impressive list of characters, including Ben Ali Gator (Fantasia), Honest John (Pinocchio), and Tony the cook (Lady and the Tramp), John also directed Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too. He was directing on The Rescuers at the time of his death on February 13, 1976.

_________________________________

|

| Remembering John – Dale Baer (1950-) |

_________________________________

John Lounsbery was described by people who knew him as modest, unassuming, quiet, unselfish, the soul of kindness, self-effacing; a gentleman. His animation stood out above the rest. His mastery of "'squash and stretch" made his work so entertaining to watch. As broad as it was, his characters were still believable, sincere, and above all, funny.

Johnny was the go-to guy for all us young people. Tweaking a few lines here and there, he'd show you how to strengthen the poses, working from what you came up with. You always left his office feeling good about yourself.

Beginning his apprenticeship under Norm Ferguson, I don't think Johnny ever forgot what it was like starting out. He was not an envious person. You never heard a bad word out of him about anyone. The one thing that showed up on a couple of occasions was insecurities about himself, which wasn't helped by some of his peers. And when you're a young guy with your own insecurities just coming into this business, it is hard to believe that someone of John's caliber and experience could feel that way too.

Johnny was being groomed to replace "Woolie," upon Reitherman's retirement, to direct. It was something John really didn't want to do. When I asked him as he was packing his office to move upstairs what it was like becoming a director, all he could say was, "I just want to be a good animator someday."

I knew Johnny only five years, not nearly long enough to absorb his 40 years of knowledge. But what I did take, I hope, was his kindness, his willingness to share, and his encouragement.

John Lounsbery never commanded respect. He earned respect by being the gentleman that he was.

_________________________________

No comments:

Post a Comment