_________________________________

_________________________________

The ultimate collection of artworks, history, memorabilia, and behind-the-scenes anecdotes every fan of The Jungle Book, one of the Disney Studios' most popular movies, will cherish.

Written by Disney Legend Andreas Deja (1957–) and lavishly illustrated, Walt Disney's The Jungle Book gathers original animation celluloids, animation drawings, and concept art—many of which have never been shown to the public—from the popular exhibition at The Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco.

Considered one of the finest and most influential Disney movie, The Jungle Book (1967) is the last animated film that Walt Disney (1901–1966) personally produced with his signature vision and footprint. This curated collection explores the nuanced complexities and challenges that were overcome throughout the film's development and production, such as the unique characters and their voice-actor counterparts, the application of cutting-edge animation techniques of the time, and the timeless, original songs by the Sherman Brothers and Terry Gilkyson. Dive into the impact of Walt's passing on the Disney Studios and the everlasting legacy of the film throughout the world.

_________________________________

Contents

_________________________________

- Foreword

- Curator's Note

- Introduction

- Story Origins

- Early Film Development

- A New Direction

- Chapter 1: A Strange Legend

- Chapter 2: A Spellbinding Squeeze

- Chapter 3: Marching Elephants

- Chapter 4: Papa Bear

- Chapter 5: Jazz in the Jungle

- Chapter 6: Tiger Trouble

- Chapter 7: Liverpudlian Buzzards

- Chapter 8: My Own Home

- Behind the Scenes

- Walt Disney's Passing

- The Sherman Brothers

- Film Release and Success

- Merchandise

- View-Master

- Legacy

_________________________________

Foreword

_________________________________

At our initial planning meeting for the museum's 34th special exhibition, Walt Disney's The Jungle Book: Making a Masterpiece, Andreas Deja, our phenomenal Guest Curator, described the tremendous impact that the film had on him in his youth. Indeed, Andreas traces the beginning of his lifelong devotion to animation and pursuit of a dream job with The Walt Disney Studios back to the first time he saw The Jungle Book in a theater in Germany. Fulfilling his vision, today, he is an esteemed Disney Legend with numerous accolades, among them the prestigious Winsor McCay Award, and is responsible for bringing to life many iconic animated characters, including Scar, Jafar, Gaston, Hercules, and Lilo–a prolific scope of work that was explored in our 2017 special exhibition, Deja View: The Art of Andreas Deja. It has been an absolute pleasure to collaborate once again with Andreas on The Jungle Book exhibition.

Andreas's first curatorial project for the museum Leading Ladies and Femmes Fatales: The Art of Marc Davis (2014), was stunning and insightful. Mickey Mouse: From Walt to the World (2019), his second curatorial project, attracted a record number of visitors to the museum. To be able to continue this dynamic partnership and friendship in mounting Walt Disney's The Jungle Book: Making a Masterpiece–to which Andreas has generously loaned never-before-seen works from his personal collection–is a true honor.

It has also been an honor to get to know, and count as friends, two additional Disney Legends, acclaimed songwriter Richard M. Sherman and trailblazing animator Floyd Norman, whose important contributions are featured in this exhibition. Richard and his late brother, Robert B. Sherman, are responsible for more motion picture musical song scores than any other songwriting team in film history, contributing to countless Disney soundtracks, including many memorable songs in The Jungle Book. Richard was one of the first visitors to the museum, has been incredibly generous to us with his time and talents, and indeed was the first recipient of the Diane Disney Miller Lifetime Achievement Award in 2015 for his outstanding impact in arts, education, community involvement, and technological advancements. Floyd has also been wonderfully generous to the museum and has visited multiple times-for special events, public programs, and the filming of his 2016 documentary, Floyd Norman: An Animated Life. In the early 1960s, as a young animator, and one of the first Black artists to work at the Disney Studios, Floyd found himself unexpectedly elevated to a story role during production of The Jungle Book. It marked an important milestone in his dynamic career at Disney, and Andreas has masterfully incorporated Floyd's early character work into the exhibition.

A precept of this exhibition is that The Jungle Book's success ultimately reinvigorated the confidence and determination of The Walt Disney Studios. It inspired the Studios' leaders, staff, and artists to continue entertaining audiences through feature animation after Walt's death in late 1966. As the museum's Diane Disney Miller Exhibition Hall celebrates its 10th year of hosting original special exhibitions, we continue to celebrate Walt's story and the impact of his creativity and innovative drive on animation, the entertainment industry, and the world.

I hope that you enjoy this inspiring exhibition, which beautifully depicts the great strides achieved with The Jungle Book and demonstrates its prominent place in animation history.

I am deeply grateful to everyone who has helped make this exhibition possible, including our donors, sponsors, lenders, members, and staff. You have my sincere thanks.

With warm regards,

Kirsten Komoroske, executive director, the Walt Disney Family Museum

_________________________________

Curator's Note

_________________________________

The Jungle Book was the very first Disney animated feature film I saw as a kid. The year was 1968, and I was 11 years old living in Germany. It is no exaggeration that this film changed my life.

I vividly remember my excitement as I watched the film's opening. Haunting jungle drums set a special mood before a mesmerizing panther, Bagheera, began to tell an intriguing tale set in India. The film's characters, like the cuddly bear Baloo, Mowgli the Man-cub, the scatting orangutan King Louie, and the ferocious tiger Shere Khan quickly came to life in my mind. I loved seeing their antics and interactions as they showed real human emotions, yet I was still aware that I was watching drawings.

This was for me! I had just discovered a new world–the world of Disney animation–and I wanted to be a part of it. At that moment, my quest to become an animator began.

I contacted The Walt Disney Studios in search of advice on how I might prepare for my future employment. I received a response in the mail, which informed me that good draftsmanship was essential for any applicant. My main focus then became learning how to draw animals and humans. A few years later, I sent samples of my artwork to Disney veteran animator Eric Larson for his evaluation. He wrote back–on Jungle Book stationery–that he thought I had what it took to join the Walt Disney Animation Studios training program.

After I joined the company in August 1980, I discovered that several of Walt's core animators, though retired from animation, were still around. Eventually, I was fortunate to get to know some of them–these were the artists who had drawn The Jungle Book. Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston told me how proud they were of the relationship they had developed between Mowgli and Baloo. Milt Kahl praised Walt's early input, even though his boss made him change the appearance of King Louie slightly. "His eyes are too small," Walt criticized. "Draw them larger!"

Sketch artist Vance Gerry talked about story problems that needed to get solved. "During production, we never knew how Mowgli's story would end," Gerry said, "until Walt suggested the young girl from the Man-village."

I was utterly fascinated to find out how The Jungle Book was made from the very artists who conceived the movie.

The exhibition Walt Disney's The Jungle Book: Making a Masterpiece showcases the film's unique production process through original animation drawings, design sketches, cels, and background art. Behind-the-scenes photos introduce the artistic staff, and documents on music and songs reveal the important contributions of the Sherman brothers.

Guest curating this exhibition has been a labor of love, and I want to thank the museum's Executive Director Kirsten Komoroske for her support and encouragement. Marina Villar Delgado and Kaitlin Buickel: Thank you for your valuable input and patience during our weekly meetings.

On a personal note, I would like to pay tribute to all of the Disney artists who produced this remarkable film. Thank you for drawing my childhood, and thank you for inspiring my career! – Andreas Deja, guest curator

_________________________________

Introduction

_________________________________

For Walt Disney Productions (also known as The Walt Disney Studios), the 1950s and 1960s were a time of significant milestones, particularly the 1955 opening of Disneyland in Anaheim, California, and the early development of Walt Disney World Resort in Lake Buena Vista, Florida. The Walt Disney Studios was the first major film company to establish its presence on television with Walt Disney's Disneyland and the Mickey Mouse Club series beginning in the mid-1950s. The popularity of animated and live-action films, including One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) and Mary Poppins (1964), was booming. With the advent of new technologies such as xerography, the Disney Studios could streamline the animation process while saving on production costs. While Disney Studios was entering a new age of production, Walt Disney's unexpected death in 1966 marked the end of an era, leaving it suddenly without the determined and innovative leader who, along with his brother Roy O. Disney, built the company from the ground up and navigated it through prior peaks and valleys.

Since 1962, Walt and the Animation Department had been working on their 19th animated feature film, The Jungle Book, a musical comedy loosely based on the 1894 Rudyard Kipling book of the same name about a young boy and his cohabitants in the jungles of India. Despite some hardships that were faced during the making of the film, it was completed and released in 1967, nearly a year after Walt Disney's passing, and is the last animated feature that Walt oversaw. The enormous worldwide success of The Jungle Book reinvigorated the confidence and pride of the Disney Studios, inspiring it to continue to entertain audiences through the art of animation without the guidance of Walt while paying tribute to his life and legacy.

This exhibition explores the complexities of the film's development and production, including the unique characters and their voice-actor counterparts, the rich artwork and use of new animation techniques, the original songs by the Sherman brothers and Terry Gilkyson, the impact of Walt's passing on The Walt Disney Studios, and the everlasting legacy of the film throughout the world.

_________________________________

Story Origins

_________________________________

English writer Joseph Rudyard Kipling's collections of stories The Jungle Book and The Second Jungle Book were first published in 1894 and 1895, respectively, and follow the adventures of Mowgli, a boy raised by wolves in the Indian jungle. The tales also feature various animals, including Baloo the bear, Bagheera the black panther, and Shere Khan the tiger, as Mowgli's friends and foes. Kipling was born in India and lived in Bombay–now known as Mumbai–until the age of six. As a child, he was fascinated by the tales and wildlife of the Indian jungle and would later draw upon Indian myths and fables in his work. As an adult, becoming a father to his first daughter–Josephine, born in 1892–is said to have been Kipling's most profound inspiration for his stories.

Kipling's stories were originally published in magazines and then compiled in the first edition of The Jungle Book. For many readers, these tales were an introduction to the culture and history of India. Rudyard Kipling lived in India for several years, but he never actually visited the jungles of Seeonee–now known as Seoni–where the stories were based; he wrote all of them while living in the United States. John Lockwood Kipling, Rudyard's father, was the first artist to bring Mowgli to life with his vivid illustrations for the first edition of The Jungle Book. The elder Kipling drew upon his experiences of having lived in India for almost 30 years. Rudyard Kipling continued to write until his death in 1936, and to this day, his stories continue to inspire adaptations in other media, including literature and music.

Despite his popularity into the 20th century and his influence on the world of literature, Rudyard Kipling's reputation remains controversial. In the Victorian era of the late 19th century, Britain regarded itself as the most powerful sovereignty in the world in terms of economy, culture, reach of empire, and political influence. Affected by his times living in Great Britain, the United States, and India, Kipling–along with others of his time–believed in upholding social hierarchies and the colonization of other countries. As a result, many of his works of fiction, including The Jungle Book, contain recurrent themes promoting colonialism and imperialism. Walt Disney, inspired by the characters and friendships those characters shared in the original material, reimagined the stories in his own way. However, despite Walt's efforts to distance himself from Kipling's original works, the film still contains insensitive materials.

_________________________________

In the early 1960s, after finishing his work on The Sword in the Stone (1963), story artist Bill Peet brought Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book to Walt Disney's attention, proposing it as their next animated film. Peet had been with The Walt Disney Studios since 1938 and was involved in some capacity with the story development, writing, or art of nearly every one of its films since Pinocchio in 1940. Peet had a heavy hand in directing the story of One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) and specialized in versatile animal personalities. Walt and Bob Thomas, a reporter and Hollywood film industry biographer, flew to Paris for a meeting about acquiring the rights to Kipling's collection of stories in 1962. At that point, Peet had already written an early treatment for the film, developed initial character designs, and devised a rough idea for the film's iconic song "The Bare Necessities."

The initial direction of the film that Peet presented was ominous and mysterious, with a storyline very similar to Kipling's collection of stories. Walt's feedback was positive on the script and storyboards, but he was dissatisfied with the dark tone. Walt insisted on moving further away from the original source material in order to make the film lighter and aimed at the family demographic. Though Peet had made a sincere effort to replicate the drama and mystery of Kipling's stories, that was simply not the story Walt Disney wanted to tell. Peet left The Walt Disney Studios in late 1964.

Artist Walt Peregoy, the lead background painter on Sleeping Beauty (1959), created a number of experimental visual development pieces for The Jungle Book. His rich, deep colors closely matched the darker tone of Peet's original story. With Disney's new direction for the film in place, he requested that Peregoy lighten and create more open space in his jungle backgrounds. Peregoy also decided to leave the Studios due to artistic disagreements, but years later joined WED Enterprises–known today as Walt Disney Imagineering–to help design EPCOT Center, fulfilling Walt's vision in Florida.

_________________________________

Walt recruited a new team to begin work on The Jungle Book. He assigned Larry Clemmons and Ralph Wright to be two of the film's writers. Clemmons had been hired by Disney in 1932 and received his first writing credit on The Reluctant Dragon in 1941, while Wright started at The Walt Disney Studios in the early 1940s and worked on many early Goofy short films. John Lounsbery, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, and Milt Kahl–four of the core animators who Walt called his "Nine Old Men"–were supervising animators on the film. Wolfgang "Woolie" Reitherman, another of the Nine Old Men, was appointed director of the film, as he had successfully made the switch from animator to codirector on Sleeping Beauty (1959). Layout artist Vance Gerry, hired in 1955 as an in-betweener, transitioned into the Story Department during the development of The Jungle Book. Layout and background artist Al Dempster, who began his career at the Studios in 1939, was responsible for many of the detailed and vivid backgrounds and concept art pieces for the film. Walt brought on songwriters Richard and Robert Sherman, known as the Sherman brothers, to match the story's lighthearted tone.

At one point Walt called a meeting with the story team, the Sherman brothers, and other regulars at the studio. According to Richard Sherman, Walt asked if the team had read Kipling's The Jungle Book. When no one raised their hands, he exclaimed, "Good! I don't want you to read it. There are some great characters in it, but it's too dark and heavy..." Walt felt that the story should remain simple and the characters should drive the story. While much of Bill Peet's story work was discarded, the personalities of the characters and the relationships between them remained in the final film.

Beginning with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937, animators studied live-action reference films to help develop and refine the movement of human and animal characters while retaining aspects of each artist's unique style. Milt Kahl noted that animating animals tended to be easier than animating humans, as viewers were generally not as critical of unnatural actions from animal characters as they are from human characters. This gave the artists more freedom of expression and experimentation in their animal drawings. Kahl noted that the goal was to learn so much about the live-action references that they no longer needed them as references, which, in turn, would make the animated actions seem more natural.

Due to the heavy character interaction in each scene and the episodic storyline, animators were responsible for specific sequences in the film rather than individual characters. The animation was transferred to celluloid sheets (or "cels") using xerography, which allowed pencil drawings to be printed directly onto cels. This copying process was adapted for animation by Disney Legend Ub Iwerks, the first animator of Mickey Mouse. Although Walt Disney initially disliked how xerography accentuated the roughness of the drawings, the process maintained the vitality of the original artwork. This technique eliminated the lengthy hand-inking stage and cut production costs significantly. Sleeping Beauty (1959) was the first film in which the technique was tested, while the first animated feature to fully utilize the process was One Hundred and One Dalmatians two years later. After Walt Peregoy left the Studios, concept artist Ken Anderson–who had been at Disney since 1934 and was one of the primary advocates for xerography–developed additional concept art and backgrounds for the film, along with ideas for character designs.

_________________________________

|

| "Many strange legends are told of these jungles of India, but none so strange as the story of a small boy named Mowgli." – Bagheera |

The story begins with the narration of one of the film's most prominent characters, Bagheera, whose name in Hindi translates roughly to "panther." Bagheera discovers the orphaned baby Mowgli in a basket after hearing his cries. After a moment of hesitation, he decides to bring Mowgli to the wolf pack, where he knows the baby will be protected–at least for the time being. In the original Kipling stories, Mowgli has a wolf mother named Raksha, which means "defense" or "protection" in Hindi. Ultimately, it is Bagheera who serves as Mowgli's main protector throughout the animated film.

Animator Hal King, best known for his work on Lady and the Tramp (1955), Sleeping Beauty (1959), and The Sword in the Stone (1963), animated the wolves, basing the wolf cubs on the puppies from One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961). English actor John Abbott voiced Akela, leader of the Seeonee wolf pack, who makes the final decision to send Mowgli on a journey back to the Man-village under the guidance of Bagheera. Akela, meaning "single" or "solitary" in Hindi, is often referred to as the "lone wolf" in Kipling's stories. Abbott, known for his Shakespearean stage roles throughout the 1930s and 1940s, was featured in pioneering BBC television broadcasts prior to World War I and moved into American television in the 1950s.

In the film, Bagheera is a wise, intelligent figure in the jungle. Throughout Kipling's stories, the panther carries scars of his past captivity and gets into many confrontations, but Walt chose to omit these elements from the film to keep the tone light. Bagheera is, however, stricter with Mowgli in the film than in Kipling's version.

Milt Kahl was responsible for much of the animation of Bagheera; in order to portray his movements, Kahl studied large cats featured in Disney's earlier live-action films. From 1948 to 1960, The Walt Disney Studios produced 14 nature and animal documentary films known as the True-Life Adventures series. The last film of the series, Jungle Cat (1960), offers a glimpse into the life of a jaguar family from the jungles of Brazil. When asked how long it took Kahl to perfect Bagheera, Kahl replied, "Oh, about two to three weeks. I looked at all kinds of big cat footage. We had done a picture called Jungle Cat; I studied that film and the outtakes as well."

Story artist Bill Peet was still at The Walt Disney Studios while early discussions about determining a voice for Bagheera were ongoing. He preferred Howard Morris, an actor best known for his role as Ernest T. Bass on The Andy Griffith Show. An interoffice memo from Woolie Reitherman to Peet responding to Peet's choice reads in part: "I would like to suggest that we let Walt listen to your latest 'Howard Morris' Bagheera. ...The animators and myself like either Karl Swenson or Sebastian Cabot for Bagheera–with Sebastian being first choice." Sebastian Cabot, an English film and television actor who voiced the narrator and Sir Ector in The Sword in the Stone, was ultimately chosen as the voice of Bagheera. Cabot would go on to narrate Disney's Winnie the Pooh series of animated films and featurettes until his death in 1977.

_________________________________

After an evening meeting at Council Rock, Bagheera accepts from the wolf pack the responsibility of taking Mowgli back to the Man-village. There is a growing threat from Shere Khan the tiger, who has returned to terrorize their part of the jungle. Mowgli, now much older, rides on Bagheera's back through the night until they stop at a tree where Bagheera believes it is safe to rest until morning. While Bagheera sleeps, a snake named Kaa slithers down from the branches to hypnotize Mowgli, putting him in mortal danger as he coils around the boy's body. Bagheera wakes up just as Kaa's mouth opens wide over Mowgli's head. Kaa hypnotizes Bagheera, and Mowgli pushes Kaa out of the tree.

Animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston brought Mowgli to life, and they studied live-action human reference footage for several scenes. Since Mowgli is one of the few human characters in the film, the animators had to be very careful in the way in they drew his actions. While they could take more liberties when animating animals, they knew that audiences would be critical if they did not capture Mowgli's movement and anatomy realistically.

Director Woolie Reitherman wanted the voice of Mowgli to sound like a typical adolescent child, but he struggled to cast the role until he found the right voice in his own home–his twelve-year-old son, Bruce. In addition to the role of Mowgli, Bruce Reitherman also voiced Christopher Robin in Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree (1966).

While Kaa in the animated film is a sly and sinister snake, Kipling's original tales included a powerful python who was one of Mowglis mentors and friends. This version of the snake character was included in Bill Peet's original story treatment of the film, but Walt changed the character concept. As a result, Kaa became a secondary antagonist. Designing Kaa was difficult due to his lack of limbs. The animators paired real-life characteristics of snakes with cartoonish elements to exaggerate his movement and personality. Thomas used Kaa's body to help convey emotions in a way that mimicked human physicality. In one scene, for instance, Kaa says something he should not have. While a limbed character in the same situation might put their hand over their mouth in embarrassment, Kaa instead puts his body in front of his mouth. In an interview discussing character animation, Thomas and Johnston recounted that Walt often told the animators that the audience watches the eyes, as they reveal what the character is thinking and feeling. Kaa's extra-large eyes, which he uses to hypnotize characters, allowed Thomas to express a wide range of emotions.

Story artists knew they could have fun with Kaa's dialogue, but as Thomas and Johnston remembered, "Our first attempts at casting for a voice unearthed much sibilance, but not enough personality." Walt found the solution by approaching one of his favorite voice actors, veteran stage and screen performer Sterling Holloway. Holloway had an illustrious voice-acting career at The Walt Disney Studios, beginning with Mr. Stork in Dumbo (1941), and at the time was already at the studio recording the lead role for an upcoming animated featurette. "Walt came to me," Holloway recalled, "and he's such a stickler for voices, and said, When you're finished with what you're doing today on Winnie the Pooh, see what you can do with a snake. I thought, wouldn't it be funny to have a snake with an aching back? Because it would be such a long ache."

The Sherman brothers worked on songs alongside story artists and decided to give the character a sinus condition, which gave an additional dimension to his hissing. Kaa's song "Trust in Me" was based on the song "The Land of Sand," which was originally written by the Shermans for Mary Poppins (1964) but went unused after its sequence in the film was cut. The Sherman brothers felt the mysteriously mesmerizing music was perfect for Kaa, so they wrote new lyrics, adding many sibilant sounds to emphasize his hissing and sinus troubles.

_________________________________

The trees start to shake rhythmically as Bagheera and Mowgli sleep. The Dawn Patrol, a group of elephants resembling a military unit, is marching through the jungle when they first meet Mowgli. The pompous Colonel Hathi leads the group of elephants alongside his wife, Winifred, and young son, Hathi, Jr. Mowgli is interested in what they are doing, so he joins the march with Hathi, Jr. The group attempts to leave in an orderly fashion, but accidentally causes a pileup when Colonel Hathi forgets to tell the herd to halt. Though the Dawn Patrol group is made up of mostly male Indian elephants, male elephants in the wild usually travel alone or in small bachelor groups.

Hathi, named after "hathi"–the Hindi word for "elephant"–was an original character in Kipling's The Jungle Book who stood for the law of the jungle. John Lounsbery was appointed directing animator for the elephant characters in the film, and was assisted by artist Eric Cleworth. Prior to The Jungle Book, Lounsbery animated characters with lively personalities and dramatic physical movements, such as chefs Tony and Joe in Lady and the Tramp (1955), Maleficent's piglike henchmen in Sleeping Beauty (1959), and the clumsy dognappers Jasper and Horace in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961). Regarding the characters he preferred to animate, Lounsbery said, "What I enjoy the most is broader action. I like the heavies. I don't like the subtle things–the princes and the queens."

Lounsbery was known for bringing oversized personalities to life, and Colonel Hathi was no exception. When Hathi, acting as drill sergeant, inspects the elephant troops, Lounsbery manipulates the loose skin around his face, squashing and stretching the character. Though the tusks on a real-life elephant are firmly connected to its skull, Hathi's tusks move alongside his mouth in a dramatic fashion as he speaks. Animation historian John Canemaker noted that despite the larger-than-life aspects of the characters he created, Lounsbery was still able to imbue them with sensitivity and heart through the subtleties of his artistic style.

In the Disney adaptation, Colonel Hathi is voiced by J. Pat O'Malley. O'Malley was a popular Disney actor who previously voiced The Colonel and Jasper in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961). In The Jungle Book, he also voiced Buzzie the vulture. Young actor Clint Howard provided the voice of Colonel Hathi's son, as well as Roo in Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree (1966) and Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day (1968). Belonging to the prolific Howard family of actors, he is the son of actors Rance Howard and Jean Speegle Howard, the brother of actor and filmmaker Ron Howard, and the uncle of actor and director Bryce Dallas Howard. Disney regular Verna Felton–well known for her roles as the Fairy Godmother in Cinderella (1950), the Queen of Hearts in Alice in Wonderland (1951), and Flora the good fairy in Sleeping Beauty (1959)–voiced Winifred, the matriarch of the Dawn Patrol.

_________________________________

After Mowgli's encounter with Colonel Hathi and the elephant troop, he earns a scolding from Bagheera, who remains insistent that he belongs in the Man-village. Mowgli decides to set off on his own into the jungle. Still angry, he sits by a rock and pouts, leading to his first encounter with Baloo the bear. Baloo cheers Mowgli up by teaching him to fight, eat, and relax like a bear. The pair dance and sing to what is arguably the most iconic song in the film, "The Bare Necessities," which preaches the importance of letting go of worries and focusing on the simple, essential things in life. Baloo thinks Mowgli should stay in the jungle, much to the annoyance of Bagheera, and the boy and the bear become fast friends.

Baloo, which comes from "bhalu," or "bear" in Hindi, appears as a sloth bear that appears in both of Kipling's Jungle Book story collections, in which he is portrayed as a strict teacher of the law of the jungle for Mowgli and the wolf pack cubs. While he remains one of Mowgli's mentors in the Disney film, he is presented as a gentle, lazy, and carefree "jungle bum," according to Bagheera. Ollie Johnston was tasked with animating Baloo in his first encounter with the Man-cub. Walt acted out how he felt Baloo should move throughout the film, and Johnston included these subtleties in his animation. Johnston also studied footage of bears to accurately mimic their movements and habits. Baloo exhibits exaggerated humanlike showmanship, as in when he stacks a tower of fruit and devours it in a single bite–all while dancing–but Johnston's fluid and clear representation of his actions make his movements feel believable.

Animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston were paired to develop the relationship between Mowgli and Baloo. From their first meeting, it was clear that the characters' friendship would grow throughout the film. "You never knew where it came from, but you had a feeling of a strong friendship here, which we wanted and needed so badly for the picture," remarked Milt Kahl. The dynamic between the boy and the bear provided the much-needed emotional depth that carries the story. Mowgli affectionately refers to Baloo as "Papa Bear" as the pair grows closer. Thomas and Johnston based Baloo and Mowgli's friendship on their own close friendship and feelings of loyalty and trust toward one another. The two met at Stanford in 1931 and began decades-long careers at Disney a few years later. They worked closely together on many films and developed a friendship that would last throughout their lives. Johnston remarked that the relationship between Baloo and Mowgli was "one of the best things we've ever done."

The Studios held many auditions for Baloo's voice before deciding on comedian, actor, singer, and jazz musician Phil Harris, who Walt met at a party in Palm Springs. After coming to the studio to record test dialogue, Harris nearly dropped out of the role, claiming he was unable to perform the dialogue "like a bear." He was called back to the studio, and writer Larry Clemmons met with Harris about his concerns. Clemmons recounts "[Harris] said, I can't do the zoobies, zoobies, zabies. What is this? Zoobie-zoobie-doobie-doo, like a bear. I said 'Phil, we don't want a bear. We want Phil Harris like on The Jack Benny Show.' He said, "That I can do!"

As director Woolie Reitherman recalled: "So, we had Phil over to the studio, and once we told him not to be a bear, but to be Phil Harris, he got in front of the microphone and tore that thing apart. Harris turned out to be just perfect for the character of Baloo." The Studios gave Harris the freedom to perform Baloo the way that felt most comfortable to him, allowing him to improvise many of his lines in the film. Both Reitherman and Walt knew that Harris would be able to convey Baloo's lively personality through his own naturally warm and entertaining demeanor.

Composer Terry Gilkyson (1916–1999) wrote the original film score, which was mostly dark and moody to match Peet's original concept for the film. Though the Sherman brothers were brought on to compose all of the songs for the film, Walt did have one request of them: "I have one excellent song by Terry Gilkyson, called The Bare Necessities. That's the only one I can use. Is that okay with you two?" The pair agreed, as the song fit the upbeat nature of the film. "The Bare Necessities," sung by Baloo and Mowgli, was nominated for an Academy Award' in 1968 and has since been covered by artists around the world across multiple genres, formats, and media.

_________________________________

|

Chapter 5: Jazz in the Jungle (00:29:45–00:39:11)(00:32:19–00:33:45)(00:33:46–00:36:29 / 00:53:20–00:53:37 / 00:37:48) |

Just after lazily floating down the river on Baloo's belly at the conclusion of "The Bare Necessities," Mowgli is kidnapped by a group of mischievous monkeys. The monkeys take him to their leader, King Louie, who resides in the ruins of an ancient palace. Louie, a cool, smooth-talking orangutan, hopes that Mowgli can teach him how to make fire, which he refers to as "man's red flower.' Louie makes his pitch to Mowgli in the jazz song "I Wan'na Be Like You, but his effort is in vain, as Mowgli does not know how to make fire. When Bagheera and Baloo arrive to save Mowgli, a scuffle ensues, and the pair rescue Mowgli as King Louie's palace crumbles to the ground.

Unlike most characters in The Jungle Book, King Louie was created expressly for the film. Orangutans are not native to the jungles of India, and there is no ape king in Rudyard Kipling's original stories, either. Both versions do include the "Bandar-log, a group of monkeys who live in Kipling's Seeonee jungle and end up kidnapping Mowgli, but the scene plays out quite differently in the film.

King Louie and the monkeys were brought to life by Milt Kahl, Frank Thomas, and John Lounsbery. Even during the wild, frantic action sequences, the animators maintained movements consistent with the characters' anatomy. When Baloo, disguised as an ape, grabs King Louie and throws him over his head, the bear's spine turns in a naturalistic manner. While at times exaggerated, there are no impossible distortions in either of the animals' movements throughout the sequence.

"I Wanna Be Like You" was one of the more challenging songs to write, but it also ranks among the more memorable songs from the film. In order to make the kidnapping of Mowgli into a playful–rather than somber–event, the Sherman brothers came up with a jazz melody to fit King Louie's personality as the "king of the swingers." Walt and the team first considered casting Louis Armstrong, a jazz legend who had performed at Disneyland, as the voice of King Louie. Armstrong and Walt had become friends, and Walt knew that his style and rich, gravelly voice would fit the melody of King Louie's iconic song. The team ultimately reconsidered, believing that casting an African-American actor for the voice of an ape would be inappropriate, according to Richard Sherman in a 2013 interview in the New York Times. Still, the character has long been criticized and considered an offensive caricature that utilizes racist stereotypes of the Black population.

The then-president of Walt Disney Records Jimmy Johnson suggested famed Italian American jazz trumpeter and vocalist Louis Prima because he "was this wild, swinging cat." Prima and his band, Sam Butera & The Witnesses, flew to Burbank to audition at the studio, where they performed almost everything that went into their Las Vegas act at the Hotel Sahara. During a typical performance, Prima would walk through the audience, blowing a horn as his bandmates followed in a line. "It was always the grand finale to his act." explained director Woolie Reitherman. Inspired, the animators incorporated that element of their performance into the film: King Louie mimes a trumpet with his hand and marches around while Mowgli and the other monkeys follow. The scene also includes a monkey using bananas as drumsticks mimicking the way that Prima's drummer would beat his drumsticks enthusiastically on furniture, other instruments, and the ground. "It's a hilarious bit, and it broke up the animators," remarked Johnson.

The song "I Wan'na Be Like You" includes a notable section of scat singing, a vocal improvisation technique that uses nonsense syllables. Due to Louis Prima and Phil Harris's tight schedules, they had to record their individual sections of the scat duet separately. Harris would listen to Prima's sections and then ad-lib his responses. Richard Sherman remarked, "It was hilarious, like a real scat conversation. It took a wonderful combination of artistic and technical talents to pull it off successfully."

For its 50th anniversary of the classic film, the song includes a extra section of popular celebrity Phil Collins' last verse of "Strangers Like Me" from Disney's Tarzan that shares Harris and Prima's performance. Collins also voiced Lucky the Vulture from The Jungle Book 2, produced in 2003 by DisneyToon Studios Australia and released by Walt Disney Pictures, is a direct-to-video sequel to the original film.

_________________________________

|

Chapter 6: Tiger Trouble (00:39:38–01:01:00)(00:39:38–00:47:08)(00:47:54–00:52:47)(00:54:15–01:01:00)(00:55:15–00:56:58) |

After the run-in with King Louie and the monkeys, Baloo encourages Mowgli to return to the Man-village for his own safety, and Mowgli storms off for the second time. The tone of their relationship has shifted: Mowgli now feels betrayed by Baloo. Soon after, the terrifying tiger Shere Khan makes his first appearance. While stalking a deer in the jungle, Shere Khan is interrupted by "that ridiculous Colonel Hathi" and his elephant troop's loud marching. Shere Khan overhears Bagheera talking to Colonel Hathi about Mowgli, and his hunt for the Man-cub begins.

Shere Khan is Mowgli's main antagonist in the film, as he is in Kipling's original stories. According to Kipling, "shere" translated to "tiger," while "Khan" referred to a level of distinction; the two words together can be interpreted as "chief among tigers." In both the Kipling stories and the Disney film, Shere Khan is deeply feared by most of the animals in the jungle.

Shere Khan is briefly mentioned by several characters before he appears for the first time, about two-thirds of the way through the film. The animators were curious about Shere Khan's role in the film, as the character was not talked about much in storyboard meetings up until this point. Eventually, Walt requested that Ken Anderson draw up some sketches of how he envisioned Shere Khan. Walt did not want a tiger that growled the entire time; he wanted a new type of villain. Anderson drew an overly confident, suave, and menacing character–and Walt was sold.

Shere Khan was animated primarily by Milt Kahl. As he did with Bagheera, Kahl studied earlier live-action Disney documentary films in order to incorporate the qualities of a real tiger into the animated character. He often referred to A Tiger Walks (1964), a film about a Bengal tiger that escapes from a traveling circus. Kahl paid close attention when designing the stripes on Shere Khan, using them to add volume and perspective to his motions. A powerful draftsman, Kahl played down the tiger's actions, evoking a sense of power and ferocity through poses and subtle movements. As Deja wrote in his animation biography The Nine Old Men, "The less Shere Khan moves, the more intimidating he becomes."

When considering the voice of Shere Khan, Kahl said, "They were thinking of kind of a Jack Palance type, you know. A straight evil character who was going to kill this kid, you know. And maybe enjoy him for dinner. ... Ken Anderson made one drawing; he was thinking of a supercilious, above-it-all tiger..." for which George Sanders fit the bill perfectly. Sanders, a British actor, had an upper-class English accent that was ideal for sophisticated, villainous characters. Prior to The Jungle Book, Sanders was cast in roles such as Addison DeWitt in All About Eve (1950), Richard the Lionheart in King Richard and the Crusaders (1954), and Mr. Freeze in an episode of the Batman television series (1966).

This was Sanders's last significant role before his death in 1972. Shere Khan's personality and facial expressions were based directly on Sanders, though animator and historian John Canemaker notes that Kahl drafted him to be somewhat of a caricature of himself. Though Sanders could sing–he had sung in several previous productions and even recorded an album–he was unable to sing for the role of Shere Khan. The studio brought in Bill Lee, who had sung in other Disney films, such as Alice in Wonderland (1951), One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), and Mary Poppins (1964), to sing in his place. Sound effects artist Jimmy MacDonald, the voice of Mickey Mouse from 1946 to 1977, provided Shere Khan's roars for the film.

_________________________________

After escaping the coils of Kaa for the second time, Mowgli settles on a rock in a deserted part of the jungle where a group of shaggy-haired Liverpudlian vultures pester him. Mowgli walks off, visibly upset, while the vultures sing a song in an attempt to entice him to join them as an honorary vulture. Shere Khan emerges, and Mowgli stands his ground against the tiger as he attacks. Baloo appears and grabs hold of the tiger's tail to give Mowgli, now assisted by the vultures, a chance to escape. A chase ensues. Lightning strikes a tree and sets it ablaze just in time for Mowgli to grab the one thing Shere Khan is afraid of–fire. Mowgli ties a flaming branch to the end of Shere Khan's tail, and the tiger escapes into the jungle. Baloo lies unconscious from the attack, prompting a tearful eulogy from Bagheera, until he finally wakes up–much to the surprise of Mowgli and Bagheera.

The vultures were almost entirely new characters created for the Disney film. While vultures do make a brief appearance in Kipling's stories, they mostly feed on animal carcasses. Consistent with the lighter tone of his version of the story, Walt Disney wanted the vultures to be silly and fun. During the production of the film, Beatlemania was in full swing. Walt originally considered having the Beatles–or a Beatles-like group–voice the vultures and perform songs for The Jungle Book, but the idea was ultimately abandoned. Milt Kahl, Eric Larson, and John Lounsbery worked on the animation of the vultures, who retained their original Beatles-inspired mop-top design and vocal accents.

The group of vultures were originally intended to sing a rock-and-roll rendition of "That's What Friends Are For"–initially called "We're Your Friends"–but Walt concluded that a contemporary rock song would give the film a short shelf life. The Sherman brothers instead turned the vultures into a barbershop quartet while still paying homage to the British Invasion, later noting that "Walt thought that was a very funny idea and went for it in a big way." Buzzie, the leader of the vultures, was voiced by J. Pat O'Malley, who also voiced Colonel Hathi. True to their personalities, Flaps was voiced by English musician Chad Stuart of the folk-rock duo Chad & Jeremy, Ziggy was voiced by English actor Digby Wolfe, and Dizzy was voiced by Lord Tim Hudson, an Englishman who made a name for himself as a DJ in Canada and the United States.

Shere Khan perishes in a stampede of buffalo in Kipling's story "Tiger! Tiger!" but flees into the jungle in the Disney film. For the end of the scene following the defeat of Shere Khan, director Woolie Reitherman recalled that it was a Disney story invention to have everyone believe that Baloo had been killed. He said, "Not only does Mowgli think he is killed, but so does the panther. Then, Bagheera eulogizes his dead companion, but then the dead companion wakes up and wants more and more of the eulogy." Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston once again took special care to articulate the friendship of Baloo and Bagheera based on their own closeness, and sadness quickly turns to happiness as it is revealed that Baloo has survived.

_________________________________

With the threat of Shere Khan removed, the unlikely trio of Mowgli, Bagheera, and Baloo set off merrily into the jungle. Hearing singing in the distance, Mowgli pecks over the brush to find a girl fetching water to bring back to the Man-village. Intrigued, Mowgli moves closer to get a better look, as he has never seen another human. The girl charms Mowgli into joining her at the Man-village despite Baloo's initial apprehension. Comforted knowing that Mowgli is now safe with his own kind, Bagheera and Baloo cheerfully dance off into the jungle together: "Well, come on, Baggy, buddy, let's get back to where we belong."

Through most of production, the animators had no idea how the film was going to end, as they had each been focusing on developing specific sequences and gags. They knew that Mowgli would make it back to the Man-village one way or another but could not fathom why he would give up on his dreams of staying in the jungle with his friends. Walt brought the team together and suggested that Mowgli would be enticed to join the Man-village by a young girl around his age. Walt's suggestion was initially not well received by the animators, as they believed Mowgli was too young to show any interest in a girl, so the ending would not be believable or true to his character. Despite their doubts, Walt knew this was how he needed the film to end. According to Woolie Reitherman, "Walt liked people around him that were willing to try and dare, even though they didn't know quite where they were going or why."

Kipling's stories do not feature a young girl, but rather an adult woman named Messua, who is Mowgli's adoptive mother. Ollie Johnston, who was tasked with animating the girl in the sequence, felt that the ending was a clumsy afterthought at first. However, the more he worked on it, the more he saw the scene come to life, thanks to the endearing and natural innocence of the characters. Animator Floyd Norman, who worked with Larry Clemmons on the story for the film, reflected on the ending and the interaction between Mowgli and the girl: "You never think of Mowgli being a kid. He sees the girl. The girl is enticing. And he follows her. Maybe it's just curiosity. He had never seen a girl before. It's charming. It's cute, and it's our ending. Your solutions to problems in films sometimes are very simple. It was a simple solution that we thought was to a complex problem."

Once Walt decided on a rough conclusion to the film, the Sherman brothers wrote the haunting ballad for the girl, titled "My Own Home." Child actor and singer Darleen Carr; who had already starred in a number of television shows, was at the studio filming Monkeys, Go Home! (1967) while The Jungle Book (1967) was in production. Carr was asked to record a demo of "My Own Home," and Walt, impressed, cast her in the role. The Sherman brothers incorporated the melody of the song into the film in such a way that it became the main theme throughout, beginning with the wolves finding baby Mowgli in a basket.

Once Johnston had finished a few scenes for the final sequence of the film, he brought them to Walt's office for review and inadvertently walked into a disagreement between Walt and Milt Kahl about whether or not tigers could climb trees: Kahl thought they could not, and Walt thought they could. Johnston initially feared that Walt would be too worked up to be receptive to the tender mood of his scene, but he was relieved when Walt ultimately gave it his stamp of approval. Johnston later told Deja, "Incidentally, Milt happened to be right: Tigers do not climb trees." (In fact, tigers can climb trees, but they seldom do so after they have reached adulthood.)

Throughout the development of the film, Walt reiterated how he wanted the team to focus on the characters while he focused on the story. Because he was being pulled in many directions by a number of key projects at the time, some doubted his ability to successfully give The Jungle Book his full attention and see the storyline through to the end. However, the film's creative team trusted Walt to lead them in the right direction. The film's overall story outline proved once again that Walt was one of the greatest storytellers of all time. The Sherman brothers noted, "He was on top of every sequence of every animated movie that was ever made under his name. And he would constantly make them better."

_________________________________

Walt was involved in a number of projects in the mid-1960s besides The Jungle Book. He was especially passionate about the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, or EPCOT, intended as part of his ambitious "Florida Project" which would open as the Walt Disney World Resort in 1971. In 1966, however, he began feeling weak and tried to hide his frequent pain. Animators believed he was suffering the effects from an injury sustained while playing polo several decades earlier. The Jungle Book was the last animated production that Walt personally supervised before passing away from complications related to lung cancer on December 15, 1966, at the age of 65. In a 2016 interview, animator Floyd Norman reflected on Walt's sudden death: "None of us knew during the making of [The Jungle Book] that Walt was sick. He worked with the usual vigor and enthusiasm. You would never think Walt was a dying man in 1966. He never came across as faltering or that his health was failing. We never got that. I think that's why his passing was a shock to all of us." Walt's death was mourned at The Walt Disney Studios and all over the world.

At the time of Walt's passing, The Jungle Book was only half finished. Everything Walt had learned from the past 30 years of filmmaking was poured into the project: Unique character personalities, sight gags, catchy music, rich background art, and more. His passing led to mass uncertainty at The Walt Disney Studios, even halting production. Animators and key personnel became concerned about the future of animated filmmaking, while management briefly considered shutting down the Animation Department to rely on income generated solely through rereleases of older films. Before his death, Walt personally asked Woolie Reitherman to help lead the feature film animation program, so Reitherman pushed back against the shutdown. He and the other artists wanted the film to be completed the way Walt wanted, and they were ultimately able to continue production.

Before its official release, the film was screened at the studio. 'The audience included Hazel George, Walt's personal nurse and one of his closest confidantes. Ollie Johnston recalled talking to her after the screening: "She said, 'Walt wasn't a man, he was a force of nature. And that last scene where Baloo and Bagheera dance off into the sunset, she says, 'You know, that's just the way Walt went off. He went off into the sunset. Just like that, here he's gone."

The tremendous success of The Jungle Book reestablished animation as a valuable form of storytelling while also reassuring The Walt Disney Studios that they would be able to move forward without their ambitious leader. Walt was never as concerned with profits as he was with entertaining audiences with the art of great storytelling. Reflecting on this time, Reitherman said '"... [Walt] left so many roots in all of us. All of the pictures I did since then, I went for personality, strong characterization, strong voices that fit the character. And it did make the pictures ever so much simpler to construct," This simplicity also helped save the company money on production costs for the next decade.

In the wake of Walt's death, the animators united to preserve what he had worked so hard to create. Reitherman continued, "There was no replacement for Walt. In my view, the main thing was to keep this team together and keep the same creative juices flowing..." Reitherman remained in key roles at the Studios until his retirement in 1981, directing or codirecting films such as Robin Hood (1973), The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (1977), and The Rescuers (1977). During this time, he and the other animators reestablished a training program for young artists to guarantee the future of animation at the Studios. "This was survival, as far as I and most of the animators were concerned. It was survival to keep this thing going, this thing called 'Walt Disney Animation.'"

_________________________________

|

The Sherman Brothers |

Brothers Robert and Richard Sherman began writing music together in 1951. By 1960, the duo had written a number of hits that caught the ear of Walt Disney, particularly "Tall Paul," co-written with Bob Roberts, in 1958. It was recorded first by Mouseketeer Judy Harriet and later became a top-ten hit for Mouseketeer Annette Funicello. Shortly thereafter, Walt hired the Sherman brothers as members of his creative team, and by 1967, they had written songs for many Disney films and television shows, including The Absent-Minded Professor (1961), Mary Poppins (1964), and The Happiest Millionaire (1967). One of their most popular songs, "It's a Small World," was written for the eponymous attraction from the 1964–1965 New York World's Fair, and still plays in it's a small world attractions at Disney parks around the world. The Sherman brothers have written more Disney film songs than any other songwriters in history.

After storyboard artist Bill Peet left the studio, Walt asked the Sherman brothers to compose all new songs for The Jungle Book, with the exception of "The Bare Necessities, as many of the songs composed by American folk artist Terry Gilkyson were more suited for Peet's original, darker tone. The Sherman brothers composed seven original songs that fit the lighthearted tone Walt envisioned. George Bruns, who had written music for several other Disney films, composed the instrumental score. Though The Jungle Book was a feature in which the personalities of the voice actors influenced the design of the characters, the songs for the film were written before the voice actors had been chosen. Through their music, the Sherman brothers brought each character to life while making them more compelling and interesting.

After Walt's passing, they continued to compose music for the Disney parks and many Disney films, including The Aristocats (1970), Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971), and several Winnie the Pooh featurettes. The Sherman brothers were named Disney Legends in 1990, were inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2005, and received the National Medal of Arts in 2008.

_________________________________

|

Film Release and Success |

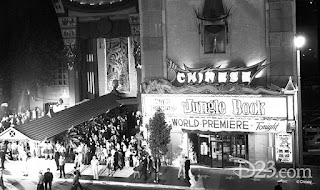

In October 1967, 10 months after Walt's passing, excitement grew in anticipation of the theatrical release of The Jungle Book. The Walt Disney Studios hoped they had properly honored Walt's life, work, and vision. On October 18, the film's gala premiere was held at Hollywood's famed Grauman's Chinese Theatre as a benefit for the Los Angeles Zoo. Along with the notable voice actors from the film, a number of celebrities attended the event, including actors Charlton Heston and Fred MacMurray and pop singers Sonny & Cher. Children were interviewed by famed television host Art Linkletter–more than 12 years after he helped helm Walt's opening-day broadcast at Disneyland–as part of the live coverage of the premiere.

When the film opened to wide release, it received overwhelmingly positive reviews from critics. A December 23 article in the New York Times promoted the film: MERRY CHRISTMAS right back to the Walt Disney studio!

A perfectly dandy cartoon feature, The Jungle Book, scooted into local theaters yesterday just ahead of the big day, and it's ideal for the children. Based loosely on Rudyard Kipling's "Mowgli" stories, this glowing little picture should be grand fun for all ages, for in spirit, flavor and superb personification of animals, the old Disney specialty, the new film suggests that bygone [1941] Disney masterpiece, Dumbo.

By this time, The Walt Disney Studios had come full circle with their animated films. Early Disney productions included short cartoons with gags and simple linear events to drive the storyline, but then transitioned to full character animation with complex storylines based on classic literature and fairy tales. Following World War Il, a time when the Studios experimented with different types of animation, the films became simpler and included more character-driven storylines. After Walt passed, nostalgia built for older Disney films, with Time magazine noting that the film was "...the happiest way to remember Walt Disney." Life magazine echoed the New York Times, claiming that it was the best Disney film since Dumbo (1941). Overall, critics and audiences were drawn to the animation style, rich artwork, simple storyline, and catchy songs from the film.

Produced on a modest budget, The Jungle Book became a box-office sensation. The film was rereleased theatrically in North America three times–in 1978, 1984, and 1990. Legendary actor Gregory Peck, president of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences when The Jungle Book was originally released, was so impressed that he lobbied for it to be nominated for an Academy Award* for Best Picture, though he was unsuccessful. Overseas, the film had similar success, and was rereleased theatrically in Europe several times in the 1970s and 1980s. In Germany, The Jungle Book, premiering over a year after its domestic release, was equally successful during its opening weekend, and currently stands as the most-attended film in German theatrical history.

_________________________________

Merchandise

_________________________________

The Walt Disney Studios began producing Mickey Mouse and other signature character merchandise in the early 1930s. Marketing executive Kay Kamen became Disney's exclusive merchandiser in 1932, and elevated the development and production of merchandise tied to the short cartoons. Kamen's brilliant merchandise campaign for the box office triumph Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) created a multitude of products for both children and adults. The profits from Snow White and the subsequent merchandising sales helped finance the construction of a new, state-of-the-art studio in Burbank, California. The Walt Disney Studios' new lot opened in 1940 and remains the company's headquarters to this day. Kamen worked with the Disney Studios until his death in 1949, laying a solid foundation for the development of film-and character-related merchandise and allowing Disney to oversee products and license film characters to various outlets to generate additional revenue.

With the release of The Jungle Book came the sale of a large variety of products featuring the film's most popular characters: board games, mugs, figurines, sticker pages, coloring books, and more. Simon & Schuster and its partner Western Printing and Lithographing developed the wonderfully illustrated Little Golden Books series for children in 1942 that would feature the stories of many Disney productions, including The Jungle Book. In the era of video gaming, The Jungle Book has been the basis for several releases across various platforms. Due to the film's popularity and later adaptations, merchandise based on The Jungle Book is still being produced to this day.

The film's popular and highly acclaimed songs led to the release of different versions of the soundtrack, beginning with the "Storyteller" version Walt Disney Presents the Story and Songs of The Jungle Book in 1967. This version was narrated by actor Dallas McKennon and accompanied by dialogue and sound effects from the film. The soundtrack was eventually certified Gold and nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Recording for Children in 1968.

Inspired by the success of the original Jungle Book soundtracks, Disneyland Records released an album titled More Jungle Book in 1969, an unofficial sequel written by original Jungle Book screenwriter Larry Clemmons. Louis Prima and Phil Harris reprised their respective roles as King Louie and Baloo on the album. Additional soundtracks include The Jungle Book original cast soundtrack and a jazz version titled Songs from Walt Disney's The Jungle Book and Other Jungle Favorites. The original soundtrack was reissued in 1997 to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the film and subsequent reissues have included bonus tracks.

Starting in the 1980s, home video became another avenue for Disney merchandising. 20 years after the film's theatrical release, the popular Disney's Sing-A-Long Songs home video series featured "The Bare Necessities" and "I Wan'na Be Like You." Four years later, The Jungle Book was released on VHS as part of the Walt Disney Classics series.

_________________________________

View-Master

_________________________________

The View-Master, a handheld stereoscope that allows for the viewing of three-dimensional photographs by clicking through reels, was introduced at the New York World's Fair in 1939. William Gruber invented the View-Master system in conjunction with Harold Graves, the president of Sawyer's Photographic Services. They capitalized on their license with The Walt Disney Studios to produce popular 3D reels and packets devoted to Disney's animated characters, live-action feature films and television shows, and the newly opened Disneyland.

Joe Liptak, the creator of the majority of Disney's View-Master 3D story sets for over 45 years, is revered for his exceptional artistry. The Walt Disney Studios provided Liptak with copies of production and story art, allowing him to maintain character integrity. Liptak had the ability to capture the characters' on-model look, and he took great pride in never having any of his sculptures returned for revisions. Due to the meticulous care put into the sculpting of these delightful characters, Walt Disney's story of The Jungle Book became a View-Master favorite.

Florence Thomas, one of the first and most prolific View-Master artists, specialized in the sculpting of fairy-tale scenes and helped sculpt the smaller details of some of the earlier Disney dioramas photographed for View-Master reels, including ones based on Cinderella (1950) and The Sword in the Stone (1963).

_________________________________

Legacy

_________________________________

The success of The Jungle Book (1967) persisted for decades, with multiple re-releases and spin-offs worldwide, including the 1990 animated series TaleSpin, featuring Baloo, Shere Khan, and King Louie and the 1994 live-action version of Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book starring Jason Scott Lee, Cary Elwes, Lena Headey, Sam Neill, and John Cleese opposite a cast of live animals. The Jungle Book 2, produced in 2003 by DisneyToon Studios Australia and released by Walt Disney Pictures, is a direct-to-video sequel to the original film that focuses on Shere Khan seeking revenge on Mowgli, Bagheera, and Baloo. Popular celebrities voiced the characters in the film, including Haley Joel Osment as Mowgli, John Goodman as Baloo, and Phil Collins as Lucky the vulture. Disney released a live-action and CGI reimagining of the 1967 film in 2016, directed and coproduced by Disney Legend Jon Favreau, which achieved both critical and commercial success. Richard Sherman wrote new verses for the song "I Wanna Be Like You" for the film. It won an 2017 Academy Award' for Best Visual Effects, a vindication of sorts for Gregory Peck's advocacy of the original animated film nearly 50 years earlier.

The film's enduring popularity can also be felt at the Disney parks & Resorts, where characters, songs, and scenes from The Jungle Book have been featured in walk-around character meet-and-greets, attractions, parades, stage shows, nighttime spectaculars, and more.

Rudyard Kipling's original stories in The Jungle Book have also frequently been adapted worldwide. Notable examples include the animated Maugli, or Adventures of Mowgli, a series of short films released in Russia from 1967 to 1971, and the animated Japanese/Italian television series Janguru Bukku Shönen Moguri, which originally ran from 1989 to 1990. The film Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle, produced by Warner Bros. Pictures in 2018 is the latest live adaptation, which presents a dark, serious tone closer to Kipling's original stories.

The art direction and character design in The Jungle Book continue to inspire artists creating animal characters in Disney films, including Abu, lago, and Rajah in Aladdin (1992), all of the animals in The Lion King (1994), and Stitch in Lilo & Stitch (2002). According to animator Eric Goldberg, "The Jungle Book is really an animator's movie. ... It really boasts possibly the best character animation the studio ever did." Many animators including Andreas Deja, Brad Bird, and Sergio Pablos, have said that the film inspired them to enter the field of animation.

Character animator and Disney Legend Glen Keane, perhaps best known for his work on films such as The Little Mermaid (1989), Tarzan (1999), and Tangled (2010), remembers The Jungle Book being the first Disney animated film he saw with his two younger brothers: "The movie began. Shere Khan and Kaa were magic on the screen. The thought that someone actually drew those characters never crossed my mind. They were simply alive. As Shere Khan wiggled his sharp nail in Kaa's nostril, the images were embedded in my mind. Caricature, expression, comedy, and design. I never imagined that within seven years I would have the privilege of learning under the masters of this film... and what I learned was that animation starts with observation of the world around us."

Walt Disney's The Jungle Book continues to inspire many people around the world, including artists, musicians, and celebrities, and it has maintained its popularity with everyday movie fans. The film honors Walt's life and legacy as one of the greatest storytellers of his time, and to this day, it is considered by many to be one of The Walt Disney Studios' best animated films.

_________________________________

|

| "Many strange legends are told of these jungles of India, but none so strange as the story of a small boy named Mowgli." |

|

| Bagheera hopes a family of wolves will adopt baby Mowgli. |

|

| "You told me a lie, Kaa. You said I could trust you!" |

|

| "Trust in me…" |

|

| Mowgli is under Kaa's hypnotic spell. |

|

| "Just you wait till I get you in my coils!" |

|

| "Hup, two, three, four. Keep it up, two, three, four!" |

|

| "Just do what I do, but don't talk in ranks. It's against regulations." |

|

| "Gee pop, you forgot to say 'Halt!'" |

|

| Baloo teaches Mowgli about the bare necessities of life. |

|

| "You need help, and ol' Baloo's gonna learn you how to fight like a bear." |

|

| "I'm a bear like you!" |

|

| Baloo tucks Mowgli in for the night. |

|

| Monkeys throw fruit at Baloo and create chaos. |

|

| "Now, I'm the king of the swingers!" |

|

| "What I desire is Man's Red Fire to make my dream come true!" |

|

| Baloo's cover is blown when his disguise comes apart. |

|

| "You don't scare me. I won't run from anyone." |

|

| "Now, I'm going to close my eyes and count to ten. It makes the chase more interesting... for me." |

|

| Mowgli is intrigued by a girl he spots from the man-village. |

_________________________________

No comments:

Post a Comment