_________________________________

|

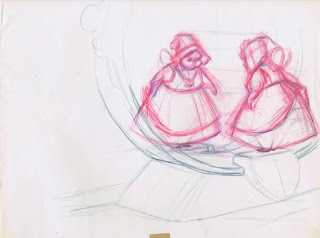

| Celebrate the legacy of Disney's core group of animators, with Walt Disney's Nine Old Men: Masters of Animation, featuring original sketches from classic films such as Pinocchio, Bambi, and Peter Pan—including an exclusive look at the animators' lives, with personal caricatures and fine artwork. |

_________________________________

In the mid-1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt coined the term "Nine Old Men" to describe the nine justices of the Supreme Court, who had seemingly lost touch with the ever-changing times. In jest, Walt Disney borrowed the term several years later to refer to his core team of animators—Les Clark (1907–1979), Marc Davis (1913–2000), Ollie Johnston (1912–2008), Milt Kahl (1909–1987), Ward Kimball (1914–2002), Eric Larson (1905–1988), John Lounsbery (1911–1976), Wolfgang "Woolie" Reitherman (1909–1985), and Frank Thomas (1912–2004)—even though they were neither old nor out of touch, and in fact would together make history with their cutting-edge contributions to the world of animation.

Produced in conjunction with The Walt Disney Family Museum's 2018 exhibition of the same name, Walt Disney's Nine Old Men: Masters of Animation features an array of fascinating artwork and family mementos from each of these accomplished gentlemen, such as sketchbooks, caricatures, and snapshots, as well as original art from the classic films Pinocchio (1940), Bambi (1942), Peter Pan (1953), Lady and the Tramp (1955), and Sleeping Beauty (1959). Personal art, paintings, sculptures, flip-books, and hundreds of original animation drawings are all faithfully presented, alongside pencil tests and final color scenes that showcase the artists' genius.

In conducting his extensive research on the Nine Old Men, curator and celebrated producer Don Hahn sat down with each of the animators' families for in-depth discussions, unearthing details about the unique personalities of the men behind iconic Disney characters and films. The result of this collaboration is a spectacular collection of personal artifacts and ephemera that have never been seen by the public, all of which help tell each animator's individual story and reveal how they collectively elevated animation to an art form.

After roughly 40 years of mentorship, the Nine Old Men were all named Disney Legends in 1989 in recognition of their lasting contributions, not only to The Walt Disney Studios, but to animation as a whole. This book offers a deep dive into their esteemed work and life stories—and a rich offering of the legacy they helped shape.

_________________________________

Foreword: Ron Miller

_________________________________

The first animated Disney film I remember seeing was Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), and it left an unforgettable impression on me as a young child. Eventually, in my work at The Walt Disney Company, I would come to know some of the men who worked on that film, along with other animated classics such as Pinocchio (1940), Peter Pan (1953), and Sleeping Beauty (1959). This group of talented artists, referred to as Walt Disney's Nine Old Men, were Walt's key animators and helped bring his masterful storytelling to life. Walt worked alongside the Nine Old Men, pushing their artistic boundaries to create Disney's timeless and beloved style of animation.

During my time at The Walt Disney Studios, I produced live-action films. When I became involved with Walt Disney Animation after Walt's passing, I knew little about producing an animated film, but many of the Nine Old Men were gracious enough to guide me in the process. The first animated feature I worked on was The Fox and the Hound (1981), which was also the last film the remaining members of the Nine Old Men were involved in. They helped mold the story and led the new group of talented animators during early stages of production. Many of the young animators who were fortunate to have been mentored by these key artists went on to be leaders in the animation and film industries. For me, The Fox and the Hound would come to represent the past, present, and future of Walt Disney Animation. I am grateful that I was able to know—and learn from—the artists featured in this exhibition.

Walt Disney's Nine Old Men: Masters of Animation allows visitors to understand the impact that these artists had on the Studios' culture, animation techniques, and the next generation of animators. My wife, Diane Disney Miller, established The Walt Disney Family Museum in 2009 not only to tell Walt Disney's true story but also to celebrate the lives and works of artists who worked with or were influenced by her father. I am honored to carry on Diane's tradition and continue her legacy of preserving the history of animation.

— Ron Miller, president of the Board, the Walt Disney Family Museum

_________________________________

Foreword: Kirsten Komoroske

_________________________________

It brings me great pleasure to share with you Walt Disney's Nine Old Men: Masters of Animation, the catalog for the retrospective exhibition at The Walt Disney Family Museum. The exhibition showcases the artists who became a cornerstone of Walt Disney Animation and continue to influence the animation industry today. Masters of Animation is curated by museum advisory committee member, dear friend, and Academy Award®-nominated producer, Don Hahn.

Don began his career at The Walt Disney Studios in the mid-1970s as a summer intern-he would bring coffee to many of the talented animators featured in this exhibition and ask questions about their work. These men inspired Don to enter the world of animation. Joining the Studios as an assistant director years later, working for Woolie Reitherman on The Fox and the Hound (1981), Don would later be mentored by the remaining members of the Nine Old Men. Ultimately producing some of Disney's most well-known films, Don's time with these famed animators left a lasting impact and influence on his filmmaking.

Don is an accomplished producer, filmmaker, author, artist, and musician who has graciously given his time to the museum and our mission of promoting innovation, education, and inspiration. Beginning in 2010, and through a series of public programs, Don has shared his deep knowledge of filmmaking and animation history with our visitors. In 2009, he produced the heartfelt film Christmas with Walt Disney, which plays exclusively in our theater every holiday season. Don has also served on our advisory committee since its inception in 2015. In that same year, Don guest-curated the museum's retrospective of animator Mel Shaw's work, and produced a fundraising gala in honor of songwriter and composer Richard Sherman.

With Masters of Animation, Don has applied his energy and talent to curating a rich and comprehensive exhibition about a group of diverse artists who helped define the standard of Disney animation. The exhibition imparts a unique understanding of these nine individual artists, and, thanks to the efforts of Don, we are able to tell these stories with original character sketches, family mementos, and never-before-seen artwork from each of these talented animators. A true friend of the museum, we deeply appreciate Don's involvement at every level.

We hope you find inspiration in the work of these legendary artists. Please accept my sincere gratitude for your support of The Walt Disney Family Museum.

— Kirsten Komoroske, executive director, the Walt Disney Family Museum

_________________________________

Curator's Note: Don Hahn

_________________________________

Animation is an artistic movement. Animators, especially Walt Disney's animators, were part of a movement that can stand alongside the impressionists, cubists, surrealists, and other artistic innovators of the twentieth century. And the Nine Old Men are its master artists, the ones who took the art form to new and unexpected heights. Yet there has been no exhibition of their personal and professional work to validate their genius—until now.

Curating a show for nine prolific twentieth-century artists has been incredibly joyful and seriously challenging. I knew most of these artists personally and worked closely with a few, so when it came time to curate the first exhibition of their work, I turned to their families to gather their personal art, much of which has never been seen by the public.

Additionally, the Walt Disney Animation Research Library, Walt Disney Imagineering, and the Walt Disney Archives Photo Library loaned generously from their collections to showcase the professional accomplishments of these brilliant artists, who, with their colleagues at The Walt Disney Studios, took the crude craft of cartooning and turned it into an art form that continues to revolutionize filmmaking today.

The Nine Old Men gave generously to future animators—a fact that supplies an important epilogue to their story. Today, the animation industry is on fire because these artists passed on their fundamental skills to a new generation. Today's modern animated features owe a debt of gratitude to these pioneering artists, who led with their genius for storytelling and their astounding craft of acting with a pencil on paper.

I owe special thanks to Ron Miller, president of the board and Kirsten Komoroske, executive director, for asking me to curate this show for The Walt Disney Family Museum; it has been a privilege. Thank you to my friends Andreas Deja and Charles Solomon, who contributed their wisdom and knowledge to the exhibition, and to the entire staff at The Walt Disney Family Museum, who endured my late-night emails to achieve the incredible task of mounting nine exhibits simultaneously. You have my respect and thanks always. — Don Hahn, exhibition curator, filmmaker, producer, author

_________________________________

|

| About Don Hahn (1955-) |

Don Hahn has experienced the past, the present, and the future of The Walt Disney Company in a way very few others have.

Born in Chicago, Illinois, and raised in Southern California, Don developed an interest in both music and animation early on. "My favorite films were One Hundred and One Dalmatians and The Jungle Book," he recalls. "When I was a kid, we went and saw those at the drive-in, in the Rambler station wagon. We put our pajamas on, my dad would back up the station wagon, the tailgate would come down, and we would watch The Jungle Book." In high school, he was as a member of the Los Angeles Junior Philharmonic, and he eventually studied music and art at Cal State Northridge.

He considered a career as a music teacher, but the pull of animation was just too strong, and in 1976, he found his way onto The Walt DisneyStudios lot for a summer job delivering coffee and art to Disney animators. Several of Walt's "Nine Old Men"—future Disney Legends such as Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, and Wolfgang "Woolie" Reitherman—were still at the Studios at the time and became Don's mentors. "It just became my university," he explains, "a place where I learned about art and music and painting and how hard it is and how great it is."

Eventually, he took on his first animation assignment, serving as an inbetweener on Pete's Dragon (1977)—followed by work as an assistant director or production manager on a host of other animated projects, including The Fox and the Hound (1981), Mickey's Christmas Carol (1983), The Black Cauldron (1985), and The Great Mouse Detective (1986). Then came a move to London, where Don took on a slightly different role as associate producer on Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988). Next, he produced the Roger Rabbit short Tummy Trouble (1989).

This shift would prove fortuitous; soon, Don was tasked with producing Disney's 30th full- length animated feature, 1991's Beauty and the Beast. Upon its release, the film was lauded by audiences and critics alike. Perhaps most notably, it was the very first animated film ever nominated for the Best Picture Oscar®. "It's probably the most emotional, and fondly remembered, project in my life," he says. "Working with people like Howard Ashman and Alan Menken, and the directors Kirk Wise and Gary Trousdale, makes you realize that there's a big safety net at Disney of talented people—and if you don't have an answer, they will."

Don followed Beauty and the Beast with 1994's Oscar-winning The Lion King, which became the most successful film in Disney history upon its release. He'd go on to produce films including The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996) and Atlantis: The Lost Empire (2001). For Fantasia/2000 (1999), he directed the host sequences featuring Angela Lansbury, Bette Midler, and James Earl Jones, among other stars. He also holds executive producer credits on The Emperor's New Groove (2000) and Frankenweenie (2012), as well as on The Haunted Mansion (2003), Maleficent (2014), and the live-action reimagining of Beauty and the Beast (2017).

Don's filmmaking eye soon shifted toward documentaries, and he made his directorial debut with Waking Sleeping Beauty (2010)—a fascinating and candid look at Disney's 1980s and '90s "animation renaissance." Other documentary projects include Hand Held (2010), which chronicles the life of Disney Legend Howard Ashman. For Disneynature, Don has served as executive producer on Earth (2009), Oceans (2010), African Cats (2011), and Chimpanzee (2012), which he also co-wrote. He has also penned several books, including Dancing Corndogs in the Night (1999) and The Alchemy of Animation (2008).

With a career this vast and varied, it's no wonder Don's been honored with numerous accolades—including two Golden Globes®, a Golden Satellite Award, the Friz Award for Animation and Family Films, multiple Annie Awards (including the prestigious June Foray Award in 2016), and a Los Angeles-Area Emmy® Award.

The sheer breadth of memorable experiences he's has had at the Company is not lost on him. "I've worked with a lot of really interesting people," Don concedes. "It's not a solo act, especially in animation—it's a team sport. And boy, at its best, it's a wonderful team sport, full of great people."

_________________________________

_________________________________

|

Introduction: The Nine Old Men |

Walt Disney called them "the Nine Old Men," playing off of Franklin Roosevelt's disgruntled description of the U.S. Supreme Court. Walt's nine—Les Clark (1907–1979), Marc Davis (1913–2000), Ollie Johnston (1912–2008), Milt Kahl (1909–1987), Ward Kimball (1914–2002), Eric Larson (1905–1988), John Lounsbery (1911–1976), Woolie Reitherman (1909–1985), and Frank Thomas (1912–2004)—were anything but old or disgruntled, however. They had become the core of his animation studio and the foundation of his entire enterprise.

They were not the first cadre of Disney animators. An earlier group of artists had been the leaders of Walt's initial triumphs, from Steamboat Willie (1928) to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937): Art Babbitt (1907–1992), Norm Ferguson (1902–1957), Ub Iwerks (1901–1971), Ham Luske (1903–1968), Fred Moore (1911–1952), and Bill Tytla (1904–1968). These veteran artists trained the Nine Old Men, who later replaced them.

Unlike their predecessors, many of whom were self-taught cartoonists, the Nine Old Men were graduates of some of the nation's leading art schools. Woolie and Ward wanted to be watercolorists; Marc was interested in animal anatomy. Unable to find work during the Depression, they answered the ads reading "Walt Disney is looking for artists."

These weren't the only artists on whom Walt relied. There were dozens of other key artists—men and women—who worked at The Walt Disney Studios alongside the Nine Old Men. People like head of the Character Model Department Joe Grant (1908–2005), story artist Bill Peet (1915–2002), art director Ken Anderson (1909–1993), and concept artist/color stylist Mary Blair (1911–1978) were arguably just as crucial to the art of animation at the Studios, but it was Walt's joking term of endearment—the Nine Old Men—that stuck almost as a brand name for these nine lead animators. Historians, journalists, and other animators began using it, and the term became part of Disney lore.

It's not clear if the Nine Old Men really saw themselves as a group. They were united by their efforts to realize Walt's vision—even when that vision seemed impossible. Nevertheless, friendships and rivalries flourished among the artists. The Incredibles (2004) director Brad Bird commented, "Every time you get Frank on the subject of Milt and Milt on the subject of Frank, it's like two thoroughbreds kind of bumping each other on down the line." As Marc said, "Sometimes I think Walt's greatest achievement was getting us all to work together without killing each other."

The use of the term "Nine Old Men" has overshadowed the fact that they were not a collective entity but nine individual artists with unique strengths, interests, styles, and approaches. Marc was never without a sketchbook, Milt never carried one. Frank and Ollie were the closest of friends, as were Marc and Milt. Ollie and Ward shared a fascination with railroads. Ward and Frank played Dixieland jazz in the Firehouse Five Plus Two. Woolie and Frank went into the military during World War II, making films that were vital to the war effort, while the others stayed at the Studios.

They didn't always function as a unit, either. Some of them worked on one film but not another, depending on who Walt felt had the talents a particular project demanded. Marc was so involved in developing Bambi (1942) that he didn't work on Fantasia (1940), Pinocchio (1940), or Dumbo (1941). Walt would later shift Woolie from animating to producing and directing, move Les to television work, and assign Marc to Imagineering.

They were united by their belief in Walt's genius, and together they created some of the greatest animated films ever made. Their work remains the standard by which all animation is judged, decades after their deaths.

_________________________________

|

Eric Larson (1905–1988) |

_________________________________

Gentle and soft-spoken, Eric was the man the other artists went to when they had troubles, knowing they would find a sympathetic ear and good advice. His kind demeanor made him the logical choice to head the training program for young animators. His students—who adored him—included Brad Bird, Tim Burton, Ron Clements, Mark Henn, John Musker, John Pomeroy, and Henry Selick, all of whom became celebrated animators and directors themselves. They later joked that Eric came to resemble the paternal owl he animated in Bambi (1942). Animator and historian Andreas Deja described him as "someone you'd want to have as your grandfather." Decades later, animator Glen Keane recalled one of Eric's key tenets: "Observation is the key to what you are going to animate."

Before coming to the Studios, Eric worked in commercial art, but he also made woodblock prints, winning honorable mentions at an international exhibit in Los Angeles. In his spare time, he experimented with writing for radio. His friend Richard Creedon, a former radio writer who had moved to the Disney Story Department, encouraged him to come to the Studios.

As an animator and a director, Eric cherished the collaborative spirit he found at The Walt Disney Studios. In a 1986 interview, he reflected, "One thing about this business: Nobody is an island unto himself. We used to have a saying that everybody worked over everybody else's shoulder and in everybody else's lap. That's what impressed me about that darn place: Everybody was willing to share the knowledge they had; you didn't have to use what someone else said, but it was given without any petty feelings of superiority."

_________________________________

_________________________________

|

| Frank Thomas (1912–2004) |

_________________________________

An animator's drawings are as individual and recognizable as his signature. Frank's rough, often scribbly sketches reveal his constant striving to find the best way to depict a pose, a movement, an emotion. He stressed character and acting over fine drawing, and is best known for his skill at conveying his characters' deeply felt emotions—the dwarfs weeping at Snow White's bier or Merlin expressing awe at the power of love. Animation historian John Canemaker praised Frank's work for its sincerity: "His characters' emotions and thoughts are always believable. Captain Hook, Baloo, and Pongo have nothing in common—except the sincerity Frank gave them."

Frank was demanding of himself as he was of others. Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) animation director Richard Williams called him "as cuddly and innocent as a roll of barbed wire," a comment that Canemaker says Frank always enjoyed.

After touring South America in 1941 with Walt as part of the Disney research team dubbed "El Grupo," Frank enlisted in the Army Air Corps. He served in the First Motion Picture Unit, making training films with artists from Disney and other studios. In the military, he had fuller control of his work than he had under Walt, and he learned the importance of making a point quickly and clearly, then moving on.

Frank enjoyed playing the piano in Ward Kimball's Firehouse Five Plus Two, which provided welcome relief from the stresses of work and allowed him greater freedom of expression. His wife, Jeanette, commented on his performances: "He's a ham, that's why he's a good animator."

_________________________________

_________________________________

|

John Lounsbery (1911–1976) |

_________________________________

A quiet, self-effacing man, John was both respected and loved by his fellow artists, who praised his kindness and gentle demeanor. Some thought that his humility caused him to underplay his talent, but he let his exquisite animation speak for itself.

After graduating from East High in Denver, John worked as a lineman and pole setter for Western Union; a crack shot, he picked off rattlesnakes that threatened the other workmen. He studied briefly at the Art Institute of Denver before he switched to the Art Center School (now ArtCenter College of Design) in Los Angeles. At the suggestion of one of his professors, he responded to Walt's search for artists in 1935. John was mentored by Norm Ferguson, and they worked together on the Witch in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), but his superior draftsmanship and education led him to eclipse his mentor. An unusually versatile artist, John animated characters who ranged from the amorous Ben Ali Gator in Fantasia's "Dance of the Hours" segment (1940) to Tony and Joe in Lady and the Tramp (1955), and from the dim-witted Gideon in Pinocchio (1940) to the pompous Colonel Hathi in The Jungle Book (1967).

John loved animating. When he was promoted to director, he told director Richard Williams, "They pushed me into this thing." Animator Dale Baer, who spoke to John as he was preparing to move to the director's chair, recalled. "He said all he wanted was just to be a good animator someday."

John loved the West. He and his family lived on a six-acre ranch, where they raised chickens, horses, and cows. His ranch burned to the ground in the 1970 Chatsworth-Malibu fires, but he and his wife, Florence, rebuilt it from the ashes. His daughter, Andrea, said he "could have been a pioneer settler." His shyness, and the fact that he died before many historians began interviewing the older artists, have caused John to receive less attention than his work warrants.

_________________________________

_________________________________

|

Les Clark (1907–1979) |

_

ALICE: Yoo-hoo! Yoo-hoo!

CINDERELLA: Oh, there you are.

PINOCCHIO: Father? Father, it's me.

WENDY: Bu... But where are we going?

_________________________________

Les first met Walt and Roy Disney in 1925: He was a high school student when he served them ice cream at a candy store on Vermont Avenue. When Walt hired him two years later, he said, "You know this is only a temporary job, Les. I don't know what's going to happen." That "temporary job" would last forty-eight years, stretching from the silent-film era to the advent of television, and from the weightless "rubber hose" animation of The Skeleton Dance (1929) and the early Mickey Mouse shorts to the gracefully stylized realism of Sleeping Beauty (1959).

Because of his quiet personality, Les often garners less attention than some of the other members of the Nine Old Men. However, his work ranged from the comic intensity of Mickey bringing the brooms to life in Fantasia's "The Sorcerer's Apprentice" (1940) to the charming clumsiness of Lady as a puppy in Lady and the Tramp (1955).

After Les directed two sequences in Sleeping Beauty, Walt moved him to educational films and television, where his work included the original titles for the Disneyland program. His TV producer Ken Peterson said, "Les never settled for anything that wasn't top quality his work always had that fine finish."

Director Wilfred Jackson commented, "[Les] is a modest person, not at all inclined to blow his own horn, and you might not suspect he had an important part in what was done at the Studio just from hearing Les talk about himself … He is one of quite a few quiet, shy, talented, dedicated artists who worked hard and long, almost unseen and unheard of behind the scenes, to help make Walt's cartoons turn out the way they did."

_________________________________

_________________________________

|

Marc Davis (1913–2000) |

_________________________________

Walt referred to Marc as his "Renaissance man": He could design characters, animate, and do story work. Even by the Studios' lofty standards, Marc was an exceptional draftsman. As a young man, he sketched the animals at the Fleishhacker Zoo in San Francisco and studied books on anatomy. After a day of animating at the Studios, he would sketch the dancers, acrobats, and animals he saw on TV, or read about art history.

"If you have a hard-backed sketchbook and a fountain drawing pen, you can draw anywhere," he said—and he proved it on travels to the wilds of Papua New Guinea. Marc also experimented with lithography and painted in oils; he said he made it a point to paint a tree from nature once a year, just to remind himself "what's real."

In addition to his animation duties, Marc took over legendary instructor Don Graham's life drawing classes at the Chouinard Art Institute after World War II. Marc's character Maleficent from Sleeping Beauty (1959) was a masterstroke of draftsmanship and acting that inspired the 2014 live-action film starring Angelina Jolie. Later, after Marc completed the animation of Cruella De Vil in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), Walt moved him to Imagineering, where he applied his talents to designing attractions like Pirates of the Caribbean and Haunted Mansion for Disneyland and "it's a small world" for the 1964-65 New York World's Fair.

He summed up his approach to drawing in an interview in 1990: "Properly organized, a group of lines on paper can produce an illusion. You can make the image seem to rise out of the paper, you can make it seem round or flat. These principles underlie animation: They affect the shapes that make up the characters. It was these principles that were terribly important to Don Graham, and they're terribly important to me."

_________________________________

_________________________________

|

Milt Kahl (1909–1987) |

_________________________________

Like his best friend, Marc Davis, who was never without a sketchbook, Milt never carried one. His assistant Stan Green recalled, "When five o'clock came, he wanted nothing to do with art, which amazed me. It was all chess and fishing. I don't think he did the wire sculptures until he retired. I never saw any artwork he did outside of studio work."

Milt was regarded by some as the greatest draftsman of the nine, and the others often brought their drawings to him to refine their poses with his eye for perfection. He enjoyed puzzles, such as double acrostics, and fly fishing—the most coolly intellectual of sports. Milt was a gifted chess player, but he was also a volatile one: Any loss would likely be followed by the sound of chess pieces hitting the wall.

He also had an uncanny ability to concentrate. Nearly everyone who worked with Milt had stories about talking to him for several minutes without him realizing someone was there. In everything he did, Milt held himself to the highest standard of excellence and expected nothing less of the people around him. When other artists praised his scenes, his standard response was, "Maybe I just work a little harder."

When asked to explain how he had done something, Milt would stammer, then conclude, "You just do it!" Drawing and animation came naturally to him. As a draftsman, his only rival at the Studio was Marc, who said, "He was just such a natural for drawing. He hadn't studied a great deal—he just had it all there in the tips of his fingers right from the beginning."

_________________________________

_________________________________

|

Ollie Johnston (1912–2008) |

_________________________________

Ollie's drawings reflect his gentle, soft-spoken nature. Glen Keane, who worked as his assistant, explained that "Ollie's pencil just seemed to kiss the paper." With his usual modesty, Ollie would point to a pencil that had belonged to Fred Moore, the animator who had trained him, saying it should still have a few good drawings left in it. A warmth permeates all of Ollie's work: Mr. Smee may be a pirate, but there's not a cruel bone in his body. Even in Ollie's scene when Pinocchio lies to the Blue Fairy, the puppet may feel trapped by his own falsehoods, but he's never malicious.

Outside the Studios, Ollie was best known for his love of railroading, an interest he shared with Ward Kimball and Walt. A one-inch scale steam train ran through his yard in Flintridge. Beginning in 1962, he spent six years finding and restoring a 1901 Porter steam engine that once hauled coal; he christened it the Marie E. after his wife and installed it at his vacation home in the mountains of Julian, California. Ollie glowed with happiness when he took friends for rides on either train, and a "steam up" with the accompanying informal potluck was a coveted invitation.

In 1981, Ollie and his longtime collaborator Frank Thomas published the definitive bible on the art of animation, entitled Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life. It quickly became required reading for future generations of animators. The longest lived of the Nine Old Men, Ollie received the National Medal of the Arts from President George W. Bush in 2005, but he seemed to take greater pleasure in personal tributes from friends.

_________________________________

_________________________________

|

Ward Kimball (1914–2002) |

_________________________________

Ward was the most eccentric and flamboyant of the Nine Old Men. He favored oversized glasses and mismatched plaids, and he posed for a studio portrait wearing the paw from a gorilla suit on one hand. Although he created some of the Studios' most frenetic scenes—the Mad Tea Party in Alice in Wonderland (1951) and Donald, Panchito, and José performing the title song from The Three Caballeros (1945)—he also animated Pinocchio's beloved mentor and conscience, Jiminy Cricket.

Like Walt and Ollie Johnston, Ward was a railroad enthusiast. In 1938, he bought a full-size 1881 steam locomotive, which he restored and installed with other cars on a track at his San Gabriel home, dubbing the collection the Grizzly Flats Railroad.

Ward was also a talented painter, sculptor, caricaturist, and illustrator who delighted in swapping gag drawings with his fellow artists. When Walt would telephone on weekends, Ward would ask, "Walt who?"; When Walt replied, "Dammit. Kimball, it's Walt Disney!", Ward would ingenuously reply, "Well, I know several guys named Walt, I just wanted to know who I'm talking to."

In 1948, Ward formed the jazz band Firehouse Five Plus Two with other Disney artists, including Frank Thomas. They began playing for noon dances on the studio lot, but the group soon graduated to nightclubs and Milton Berle's and Ed Sullivan's television shows. The Simpsons producer-director and jazz musician David Silverman recalled. "When things started clicking on The Simpsons, I got a letter of encouragement and congratulations from Ward. I think he was happy to see that a new wave of animation was coming-and that at least part of the wave was cynical and sarcastic."

_________________________________

_________________________________

|

Wolfgang "Woolie" Reitherman (1909–1985) |

_________________________________

Woolie's handsome, deeply lined face gave him the look of a hero in a Joseph Conrad novel—an impression his height, broad shoulders, brilliant Aloha shirts, and cigars only strengthened. During World War II, he served with the Army Air Transport Command, flying "over the hump"—over the Himalayas to China—notoriously dangerous mission. He received the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with one bronze Oak Leaf Cluster, and he remained an aviator until his death in 1985.

Like many of his fellow Disney artists, Woolie studied at the Chouinard Art Institute before coming to the Studios. He wanted to be a watercolorist, but jobs were scarce during the Depression and Walt Disney was looking for artists.

Woolie often handled fights and action sequences at the Studios, including Monstro the whale in Pinocchio (1940), the tyrannosaurus attacking the stegosaurus in Fantasia (1940), Tramp fighting the rat in Lady and the Tramp (1955), and Prince Phillip battling the dragon in Sleeping Beauty (1959). But he was also adept at comedy, as he proved in his work for the "El Gaucho Goofy" sequence in Saludos Amigos (1942) and Ichabod Crane's gawky dance with Katrina Van Tassel in The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949).

When Walt turned his attention to television, live action, and Disneyland, he chose Woolie to serve as producer-director of the animated features. Frank Thomas said the choice was due to "energy and experience—he'd done a lot more different types of scenes." Although the Academy Award-winning director took pride in his ability to get the other artists to work together, Woolie said with typical candor, "I became a director because Walt said, "Be a director!'"

_________________________________

_________________________________