In the 1995 documentary film Frank and Ollie, Frank Thomas voiced his frustration, while looking back over his long career:

I don't think there was a day going by, where I didn't think I was in the wrong profession, that I should get out of animation. I'd get so mad at something that was going on. Part of the time it was my own inability to draw what I wanted, which all of us had. I guess every artist has that kind of a problem.

A surprisingly candid statement about professional insecurity from one of the world's top character animators. Frank Thomas might not have felt confident about his draftsmanship, but when it came to animated acting performances, he set the bar so high that very few artists ever came close to that level of excellence. Frank's characters are so alive and move in such a natural manner, they seem detached from any animator's conception, they live by themselves and make decisions on their own. Of course it is extremely difficult to achieve screen performances of such a caliber, and Frank Thomas worked harder than most at the studio, according to his colleague Ollie Johnston. While in the Disney training program, a junior animator said of Frank: "You just can't please the guy, he is never satisfied." Within the animation industry, Frank Thomas is known as the Laurence Olivier of animation.

_________________________________

|

| The Flying Mouse contains scenes of sincere emotion and pathos that appealed to Frank Thomas. "If [Disney] is going in that direction," he thought before applying for work at the studio, "there might be something there that would interest me." |

_________________________________

For the first two years at Disney from 1934 to 1936 Frank served as an in-betweener and as an assistant to the great Fred Moore. Fred had made significant breakthroughs in the art of animation, his use of squash and stretch helped Mickey Mouse to appear more believable and charming than ever before. Frank became a serious student of these new animation principles, and by 1936 he was given the chance to do a few scenes with Donald Duck for the short film Mickey's Circus.

_________________________________

|

| Captain Donald Duck feeds the circus seals … or does he? |

_________________________________

Another example of early Thomas animation is Pluto in Mickey's Elephant, also from 1936.

_________________________________

|

| Pluto shows strong emotions, he is annoyed with the antics of a little elephant. |

_________________________________

By now Frank Thomas was recognized as a new up-and-comer at the studio, who showed real talent. Walt Disney first took real notice of Frank's outstanding animation when he saw scenes of a little kid encountering a bear cub up close for the 1937 short Little Hiawatha. This moment was beautifully staged as they meet in a nose-to-nose confrontation.

_________________________________

|

| Frank Thomas' animation for Little Hiawatha caught the attention of Walt Disney himself. |

_________________________________

Frank still relied on his mentor Fred Moore for help as far as appealing draftsmanship, but the nuanced performance was all his own. Even this early on in Frank's career, his characters move with real weight. The degree of squash and stretch is just right for cartoony characters like these.

And the acting choices reveal that Frank understood and felt their emotions deeply. His philosophy about animating could be summed up as: experience the character's feeling first, then worry about the drawing aspect! In other words, it is the acting the audience will remember, the graphic presentation to a lesser degree.

When it became time to cast animators for Disney's first animated feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Frank Thomas was chosen to be a part of the dwarfs unit.

He animated the section where Snow White orders the dwarfs to wash up before dinner. They all reluctantly leave the house for the outdoor tub, each with their own characteristic walk. Another of Frank's sequences proved to be a breakthrough for animated performances. After Snow White dies, the Seven Dwarfs gather around her body grieving the loss of their beloved princess. There are tears on the screen, and there were tears in the audience. For the first time, animated characters who experience sadness and sorrow deeply affected the viewers like never before.

_________________________________

|

| Delicate facial expressions combined with subtle timing communicate believable emotions of sadness and loss. |

_________________________________

After finishing work on Snow White, Frank Thomas retuned to short films featuring Mickey Mouse. The Brave Little Tailor from 1938 includes a sequence that is often mistaken as having been animated by Fred Moore. Mickey is being presented to the King and Princess Minnie so he can tell his story about killing seven (giants) in one blow. He enthusiastically acts out the situation in which he found himself surrounded (by houseflies). "They were right on top of me, and then I let them have it," he touts. The audience believes that Mickey is a giant killer, and a huge ovation follows.

_________________________________

|

| Some of the finest character animation for Mickey Mouse can be found in The Brave Little Tailor. |

_________________________________

Those scenes are arguably the finest as far as character animation goes for Mickey Mouse. There is no doubt that Fred Moore helped out with model drawings here and there, but the acting shows pure Thomas insight and analysis. The motion ranges from very broad to subtle as Mickey exaggerates his efforts in this confrontation. Every gesture and each step the character takes shows believable weight and perspective. The audience is watching living drawings perform.

For the 1939 short film The Pointer, Frank animated Mickey facing off with a bear during a hunt. By now the famous Disney character had been given eyes with pupils, which allowed for even greater subtleties and emotional range. The comedic high point is Mickey's attempt to explain his fame to the bear in an effort to be spared.

_________________________________

|

| In The Pointer, Thomas animated Mickey encountering a huge bear; attempting to save himself, he touts his celebrity: "Why, I'm Mickey Mouse. You've heard of me, I hope."; Mickey was given eyes with pupils, allowing for greater subtleties and emotional range. |

_________________________________

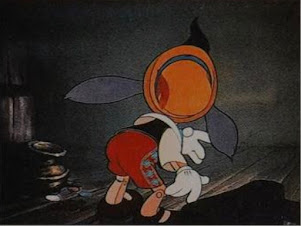

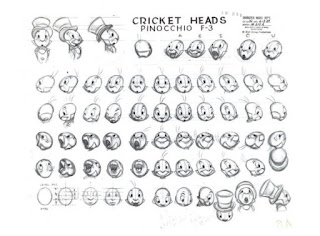

Walt Disney chose Frank Thomas to be part of the small team of animators that would supervise the animation of the character of Pinocchio. Frank's insight into the inner feelings of the living puppet helped to bring him to life during Stromboli's marionette performance. Pinocchio does his best to perform the song "I've Got No Strings," despite his total lack of experience in show business. After an embarrassing fall onstage, the audience starts to laugh at him, but Pinocchio misinterprets their reaction and claps his hands enthusiastically. The whole sequence is full of rich character moments like this one, informing us of Pinocchio's naive good nature.

During production of the film, Frank gave a lecture to fellow animators on how to animate Pinocchio physically. He pointed out that the usual use of squash and stretch is to be avoided, because the character is made out of hard wood. When Pinocchio falls and hits the ground, the body mass must not be distorted during contact, instead he just bounces off the floor. This important principle helped to remind viewers that they are looking at a puppet.

_________________________________

|

| The lack of squash and stretch when Pinocchio falls reminds audiences that he is made out of solid wood; Pinocchio gives the performance of his life on stage in Stromboli's puppet theatre, exuding the show-off joy of the amateur entertainer. |

_________________________________

Frank Thomas also animated a later sequence in the film, when Pinocchio, now with donkey ears, returns home to find Geppetto gone. He vows to Jiminy Cricket that he will find him, even after finding out that his father had been swallowed by a whale. This is an important turn in Pinocchio's character development—he is starting to show a sense of compassion and responsibility.

_________________________________

|

| Pinocchio is starting to show a sense of compassion and responsibility. |

_________________________________

Very few artists were assigned to starting development and early animation for Bambi.

_________________________________

|

| The deer in Bambi, developed by Frank Thomas and Milt Kahl, brought a rare compliment from Walt: "Thanks, fellows. Those personalities are pure gold." |

_________________________________

Frank Thomas' talents were perfectly suited for a film whose character movements needed to be based on realism, to a degree never attempted before. These deer had to be drawn with real anatomy combined with tasteful caricature. Walt asked the animators to produce test footage; it seems like he was not entirely sure if he would get the results he was hoping for. Frank did rough animation of the scene involving Thumper as he is trying to teach Bambi how to say the word "bird." In the process, Bambi mistakes a butterfly, who happens to fly by, for a bird, and he begins to chase it enthusiastically. After a few erratic moves, typical for a young faun, the butterfly lands gently on Bambi's tail. The scene communicates poetry in motion. The superb animation has elegance and an almost dance-like choreography—Disney animation at a new artistic highpoint.

_________________________________

|

| Perfectly staged and animated, this charming scene became on iconic image for the film. |

_________________________________

The very important sequence featuring Bambi and Thumper on ice was almost cut from the film as it was considered extraneous. Frank argued and fought to keep this section in the movie, knowing full well that this story material offered rich possibilities for personality animation. The contrast alone between the two characters couldn't be greater. Thumper moves like a professional skater, while Bambi keeps falling over and over again, and Thumper's instructions aren't helpful at all. Frank animated the comedic antics of these two in a completely believable way. Whether the movement is subtle or broad, there is always weight, and therefore the characters look like real creatures. Today it is difficult to imagine the film without this highly entertaining sequence.

_________________________________

|

| A rough layout pose shows Thumper's confidence on the ice. |

_________________________________

During the 1941 labor strike at The Walt Disney Studios Walt accepted an invitation by the US government to go on a goodwill tour of South America. Accompanied by a small group of artists, that trip also presented useful inspiration for the upcoming production of a series of short films based on Latin folklore and culture. Frank Thomas was a member of this traveling crew as the only animator. He helped design characters like the parrot José Carioca and the little Gauchito with his flying Burrito. Back in Burbank, Frank animated brilliant key sequences for the 1945 short film The Flying Gauchito. The main challenge was how to combine characteristics of a donkey with those of a bird for this fantasy creature.

_________________________________

|

| The final animation for The Flying Gauchito. |

_________________________________

During WWII, Frank worked on a few propaganda short films like The Winged Scourge (1943), starring the Seven Dwarfs, and Education for Death (1943), which required character animation of Adolf Hitler.

After the war Walt Disney released The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad in 1949. The film presents two very different stories: one originates from English literature, the other is an American folktale. For the Mr. Toad section, which was based on the book The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame, Frank Thomas' strong sense for character relationships came through in the sequence that introduced Toad to the audience. Rat and Mole are confronting Toad in an effort to talk some sense into their friend, who has been ignoring his responsibilities for Toad Hall. Instead he has chosen a lifestyle of carefree fun as he rides along out on the open road on his horse Cyril. The contrast between these personality duos is ideal for entertaining animation. Rat is sensible and serious, Mole is trying to be, while Toad and Cyril are utterly irresponsible without a care in the world. Rat's body language is composed and businesslike, Toad's acting shows broad, theatrical gestures that communicate a zest for life.

_________________________________

|

| Frank explores range and flexibility within Toad's body. |

_________________________________

The Ichabod Crane section offered Frank a sequence with an opportunity for all-out tour de force acting. Toward the end of the film, after attending Katrina's party, Ichabod rides home through a dark forest. It is nighttime, and the Headless Horseman is very much on his mind thanks to Brom Bones' impersonation of this legendary figure at the party. The sights and sounds of the forest bring out fear and eventually horror in Ichabod's mind, but there is always the element of comedy in the way he reacts to the intimidating surroundings. He swallows nervously, covers his head with his lanky arms, and hangs on to his horse tightly.

_________________________________

|

| Frank animated this Ichabod Crane sequence at the rate of 40 to 50 feet per week. |

_________________________________

This is not easy footage to animate—whatever Ichabod's action might be has to be coordinated with the horse's swaggering walk. Frank did this brilliantly, and it is astounding to find out that he animated this sequence at the super-fast rate of 40 to 50 feet per week. Incredible!

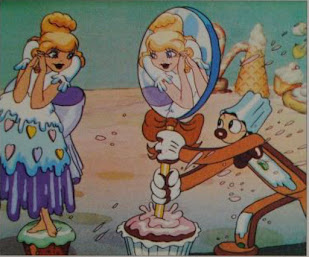

Walt Disney surprised Frank Thomas when he assigned him the villainous stepmother Lady Tremaine for the film Cinderella. "I had been known for cute, appealing characters. This was a very different kind of personality." Frank knew about the challenge it would take to bring the stepmother to life. In order to be convincing, she had to be handled subtly and realistically. He got some help from actress Eleanor Audley, whose chilling voice performance inspired Frank a great deal. She also provided live-action reference, and Frank incorporated some of her nuanced acting into his animation. Frank later commented on the dangers that live-action footage could present. If photostats (printed frames of the filmed live performance) are being traced blindly, the animation will look soft and mushy. Actors have a tendency to slowly shift their weight from one leg to the other, something that rarely works in graphic motion. The animator needs to edit the live footage and find an essence within the acting. Usually poses need to be strengthened and the timing requires more contrast. Often whole sections are not being used at all because the animator found better ways for bringing the performance across.

_________________________________

|

| A classic villain for the ages. |

_________________________________

Cinderella's stepmother is a perfect example of a villain who becomes much more evil and powerful by moving very little. Holding a certain pose or a specific expression allows the animator to show the character thinking. One of Lady Tremaine's most powerful moments occurs early on in the film, when she confronts Cinderella while having breakfast in bed. She smilingly delivers an endless list of household chores; only occasionally does she change her expression to make fierce eye contact, reinforcing her impossible demands. A classic villain for the ages.

_________________________________

|

| Lady Tremaine's subtle movements help to establish her truly evil personality. |

_________________________________

Frank Thomas animated a less realistic and much more comedic villainess for the next feature film Alice in Wonderland from 1951. The Queen of Hearts presented an interesting problem to the animator. How do you balance menace and comedy within her personality? Both were needed, and Frank struggled originally with these opposing qualities.

He eventually found a live version of this character while playing the piano with the Disney-Dixieland-Band Firehouse Five Plus Two. The group was performing on the island of Catalina when Frank spotted a heavyset lady in the audience. At times she was brash when talking to her husband, but she also had a dainty side to her when drinking a cup of tea. Frank all of a sudden had a person to base his new character on. Severe mood swings from one second to the next became a trademark for Frank's brilliant animation. When the Queen gets angry, she loses all control and gestures wildly. During her composed moments, she usually shows a fake, smirky smile.

_________________________________

|

| Thomas continued in the early 1950s to bring life to villains, such as the Queen of Hearts in Alice in Wonderland; Frank originally struggled finding the balance between the menace and the comedy for the Queen of Hearts. |

_________________________________

Because the Queen of Hearts didn't have much screen time, Frank was able to animate another character, the talking Doorknob. He interacts with Alice early on in the movie, when his door blocks the girl from following the White Rabbit. His animation is astounding, considering that this character is only a prop, an inanimate object. Frank gives him a full range of expressions, and on top of that he is able to maintain a keyhole for any mouth shape during his dialogue.

_________________________________

|

| A full range of expressions for Alice in Wonderland's talking Doorknob. |

_________________________________

There was more than one animator who wanted to draw Captain Hook, the villain in the 1953 film Peter Pan. Milt Kahl desperately lobbied for the assignment. But Walt Disney had Frank Thomas in mind, an animator with outstanding acting skills. Again there were two different character qualities that needed to work in unison. Some story artists had developed sequences showing Hook as a snobbish connoisseur of fine things, others showed him as a rough pirate.

Frank combined both approaches to create an entertaining villain, who could also be a real threat.

Through interaction with his sidekick Smee, who is also his confidant, we find out about Hook's motives. He is driven by his goal to get rid of Peter Pan. Hans Conried voiced the character and acted out scenes for the animators. Frank used some of this reference carefully, starting with Hook's introduction. He is studying a map trying to figure out Pan's hiding place. The gestures are broad when he is frustrated; they become more subtle as certain ideas come to his mind.

_________________________________

|

| Hook is looking for Peter Pan's hiding place. |

_________________________________

The animation never feels like it is based on live-action reference, the final acting choices were made by the animator.

_________________________________

|

| Captain Hook plays the piano to Tinker Bell. |

_________________________________

There are many brilliant sequences that give us insight into Hook's personality. At one point he sweet-talks Tinker Bell into revealing Pan's whereabouts. For a moment Hook becomes impatient and aggressive, but then catches himself to change his attitude again. "Continue, my dear!"

_________________________________

|

| Frank excelled at showing Hook's mood swings. |

_________________________________

Frank was excellent at portraying complex mood swings, he often used irregular eye blinks to ease into the next attitude.

For the film Lady and the Tramp, Frank Thomas animated important acting scenes with the leading dog characters. He developed Tramp along with Milt Kahl. Being a dog-owner for much of his life, Frank had already observed dog anatomy and behavior at home before he started on this assignment. In one of his memorable sequences, Tramp introduces himself to Lady, Jock, and Trusty, who are discussing the upcoming arrival of a human baby. Tramp interrupts the conversation and explains what a nuisance this newcomer to the family will be.

_________________________________

|

| In this layout sketch Frank positions the dogs effectively as a group. |

_________________________________

Frank plays off the contrast between the characters beautifully. Lady doesn't quite know what to make of this street-smart intruder, while Jock and Trusty do their best to get this pesky dog off the property. Those scenes give us great insight into their personalities.

It is not an overstatement to say that when Lady and Tramp share a spaghetti dinner in a romantic setting, movie history was made. Frank Thomas was the perfect animator to handle a sequence like this one. He turned what could have been an unappealing, messy situation into one of the greatest love scenes of all time. Beautiful draftsmanship, subtle animation, and insightful acting brought this moment to life in a way that no other animator could have done.

_________________________________

|

| One of the most charming moments ever animated. |

_________________________________

The look the two characters exchange toward the end of the dinner makes everybody believe that they have fallen in love. The scene became iconic not only for romance in film, but also for the power of Disney animation.

Frank teamed up with colleague Ollie Johnston to animate the three good fairies Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather for the film Sleeping Beauty. Both animators didn't agree with Walt Disney's original concept for these characters. He thought of them as sharing the same kind of personality, somewhat like Donald Duck's nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie. Ollie and Frank argued that contrasting characteristics would make for a much more interesting trio. So Flora became the bossy leader, Fauna takes a little time to grasp a situation, and Merryweather is the most pugnacious one.

_________________________________

|

| The three fairies have very different personalities. |

_________________________________

Perhaps because of their less realistic character design, the fairies are animated in a looser style than the rest of the cast. Their body shapes and facial features allowed for more expressive acting. Some live-action reference was used, but it is not evident in the final animated performances.

Frank helped supervise the animation of Pongo and Perdita in Disney's One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Even though many animators were by now experienced in the motion of dogs, adult Dalmatians along with a few puppies were brought to the studio for study. Frank analyzed their specific proportions as well as bone and muscle structure.

_________________________________

|

| Sketches showing the proportions and physical makeup of Dalmatians. |

_________________________________

He animated charming scenes such as Pongo and Perdita's decision to leave home to go on a search for their puppies. Later on they reunite with them in a barn in the company of cows.

One lovely scene stands out when one of the puppies, having positioned himself on top of his father, slides down his back. The way Pongo's soft skin reacts to the puppy's weight shows the believable contact between the two bodies.

_________________________________

|

| A charming moment from One Hundred and One Dalmatians. |

_________________________________

Frank also animated the dogs experiencing some difficulties when they continue their journey on a frozen creek. Trying to walk on an icy surface is something Frank was familiar with since his animation of Bambi a couple of decades earlier.

The Sword in the Stone gave Frank Thomas the opportunity to work on a variety of characters.

He animated both Merlin and Madam Mim, as they prepare for the wizards' duel. Mim sets the rules for the fight (she actually makes them up on the spur of the moment). Those scenes rank among Frank's best acting scenes ever. Mim is utterly convincing as she gestures theatrically. Merlin remains skeptical and adds a rule or two himself. As the two begin to change themselves into different animals in an attempt to outdo each other, we see Frank Thomas as an animator of action scenes. The chase is timed very sharply, and the individual transformations are inventive and entertaining.

_________________________________

|

| Those scenes, like Merlin and Madam Mim, as they prepare for the wizards' duel, rank among Frank's best acting scenes ever. |

_________________________________

Another highlight in the film was also animated by Frank. At one point Merlin magically turns himself and young Wart into squirrels. He wants the boy to find out what life is like for a small creature of the forest. Things become complicated when a young girl squirrel shows her affection for Wart. Merlin finds a female admirer as well, and both of them do their best to escape these love-struck females. The whole sequence is about love, which can be passionate, silly, or disappointing. Frank later commented that the squirrel section was one of his favorite assignments at Disney.

_________________________________

|

| This sequence from The Sword in the Stone was one of Frank's favorite Disney assignments. |

_________________________________

Frank was excellent at animating dances, and he had the chance to show this skill in the 1964 film Mary Poppins, where four penguins were paired with actor Dick Van Dyke. Since the live-action footage was filmed first, Frank needed to be very careful in his animation to avoid collisions between a penguin and Dick Van Dyke. When the actor's leg would swing sideways, the nearest penguin had to duck or jump over the leg to get out of the way. One might think that this could result in awkward choreography, but Frank actually took advantage of this challenge, and these little missteps added a wonderful and natural quality to the overall dance.

_________________________________

|

| Three of the penguins who do their best to keep up with Dick Van Dyke; The dancing penguin waiters in Mary Poppins, stole the show from Dick Van Dyke. |

_________________________________

Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston were again paired to develop the intricate relationship between the man-cub Mowgli and Baloo the bear in The Jungle Book.

After these two characters meet, Baloo tries to teach Mowgli to behave like a bear. He challenges him to a boxing match. The boy gradually takes a liking to this carefree bear, and a beautiful friendship begins. Frank animated those poignant scenes, which rival any relationship from a live action film. Eventually Bagheera, the panther, catches up with them to question Baloo's decision to take care of Mowgli. "And just how do you think he will survive?" he asks the bear. Baloo's response is hilarious. He mocks Bagheera by repeating his question: "How do you think he will... what do you mean, how do you think?" He is obviously ticked off, and Frank found just the right attitude in his animation to communicate it.

_________________________________

|

| Baloo, being upset at Bagheera, responds by mimicking him. |

_________________________________

Later in the film, Frank animated a deeply emotional scene, when Baloo is trying to tell Mowgli that he is taking him to the man village. The bear still doubts whether this was the right decision and he is trying to find the right words, anticipating Mowgli's reaction to what he is about to announce. Only a master actor like Frank is capable of portraying a character with these complex, conflicting emotions.

_________________________________

|

| The characters' contrasting attitudes communicate clearly in this one sketch. |

_________________________________

Frank Thomas' animation added a comedic touch to the sinister song "Trust In Me." Kaa, the python, tries to hypnotize Mowgli with the intention of having him for dinner. Luckily the tiger Shere Khan interrupts just in time. Frank also animated important personality scenes with King Louie, the orangutan.

The next film, The Aristocats, offered Frank a variety of character assignments. He animated the romantic get together with alley cat Thomas O'Malley and the aristocratic Duchess. The sequence never reaches the originality and entertainment of Lady and the Tramp, but the animation is believable and fun to watch. Other characters who benefitted from the Thomas touch were the butler Edgar and the geese. Frank's most memorable animation in the film is probably in the sequence that features the country dogs Napoleon and Lafayette as they try to settle for the night in their stolen motorcycle sidecar. They are constantly interrupted by Edgar, who attempts to retrieve incriminating evidence he had left at the crime scene. The two dogs act like an old couple, constantly bickering and finding fault with the other one.

_________________________________

|

| Frank's animation of Thomas O'Malley is believable and fun to watch; The two canine stars from The Aristocats. |

_________________________________

Frank Thomas admitted that working on the movie Robin Hood was not a favorite assignment. There wasn't a character he could fully develop, instead he helped out on various sequences that needed solid performances. When Robin Hood disguises himself as a stork to participate in the archery contest, Frank animated a character acting as someone else. Normally this would be an animator's dream, but the story artists didn't provide for the kind of situations that would translate into rich character animation. That being said, Frank's performance of Robin as a stork is convincing to an audience. The fact that Prince John as well as the Sheriff of Nottingham at first buy into the masquerade seems believable.

_________________________________

|

| A convincing disguise for Robin Hood. |

_________________________________

The Rescuers is a film with a cast mostly made of small critters, and Frank had his hand in animating many of them, such as the lead couple Bernard and Bianca. Mice had often taken on comedic roles in Disney animation, but these two needed to have leading star qualities.

_________________________________

|

| Reluctant agents Bernard and Bianca. |

_________________________________

Their acting became less mouse-like and more human-like in order to carry the romantic as well as the adventure elements of the story in a believable way. Frank animated the charming sequence when Bianca chooses janitor Bernard to be her co-agent for the mission to find Penny, the orphan girl. He also drew the alligators Nero and Brutus, as they chase the mice while frantically playing the organ. Many scenes with the swamp animals, including Ellie Mae and Luke were also animated by Frank.

The Fox and the Hound (1981) was Frank Thomas' final film. He worked on it for about one year, animating the pups Tod and Copper as they meet and play.

_________________________________

|

| The young Tod and Copper from The Fox and the Hound, Frank Thomas' final film. |

_________________________________

It is arguably the one sequence in the film that feels like vintage Disney. The motion is believable, and the acting is based on real children, having fun.

After retiring from animation, Frank and his friend Ollie Johnston started to write a series of important books on the techniques and philosophy of Disney animation. We are very lucky that these two men left their knowledge and wisdom in print. Animation is a complex art form that involves the study of many things, something that can be confusing and intimidating to any student of the medium. These books don't offer any shortcuts or tricks, but they spell out what is involved in becoming a top animator: observing the world around you and interpreting human and animal nature through your characters.

Frank Thomas' own animation is unique on many levels. From a technical point of view, it is interesting to note that when studying any one of Frank's scenes, it is almost impossible to find definitive key drawings—the ones that frame the action and tell the story. To Frank, every drawing was important, they were all keys to him. He hardly ever moves into what is nowadays called a "golden pose." Even within an important position, there is subtle movement to keep the animation alive. The motion never stops; perhaps that's why Frank Thomas' characters are living, breathing creations.

_________________________________

|

| The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949) (Brom Bones and Tilda) (Seq. 7: The Dance (directed by Clyde Geronimi), Sc. 36) |

Frank Thomas had been known for his fine, subtle character acting, but here he shows that he is perfectly comfortable with broad action and comedy.

During the Thanksgiving Party, Brom Bones is in pursuit of Katrina Van Tassel, who is dancing with Ichabod Crane. Brom invites little Tilda to a dance, in hopes he can swap her with Katrina. Once a dancing item, however, Tilda vehemently resists any attempts to get separated from her handsome partner. Brom's frustrated efforts to free himself lead to acrobatic as well as hilarious actions. As he tries to pull his hand from Tilda's grip, his finger elongates for one frame. It's a wonderful and surreal moment that signals that Brom Bones can't win; Tilda is impossible to shake off. As the scene continues and the motion escalates, the girl manages to stay attached to Bones, having a great time along the way.

The overlapping movement of the characters' hair and clothing helps to make this frantic dance look fluid and believable.

_________________________________

|

| Alice in Wonderland (1951) (Queen of Hearts) (Seq. 11: Trial (directed by Wilfred Jackson), Sc. 29) (01:08:05–10) |

These few rough key drawings demonstrate the Queen's volatile temperament and her abrupt mood swings. During the trial sequence, she startles Alice with her erratic reactions. At the start of the scene the Queen seems pleased: "Yes, my child..."

Then suddenly her attitude changes and she bellows: "Off with her... [head]".

She is interrupted by the little King who is pulling on her dress to get her attention in order to propose a different path for the trial.

Frank draws explosive, seemingly uncontrolled gestures before the Queen freezes in mid action. It takes her a moment to realize that she has been interrupted by somebody. The contrast in the scene's timing with its fast and slow bits surprises not only Alice, but the audience as well. A most unpredictable character!

_________________________________

|

| Peter Pan (1953) (Captain Hook) (Seq. 11: Hook Tricks Tinker Bell (directed by Clyde Geronimi), Sc. 4) (00:53:11–15) |

After capturing Tinker Bell, Captain Hook tries to gain the little pixie's trust.

He admits defeat against Peter Pan. "Tomorrow I leave the island!" he promises in a grand theatrical, almost campy gesture. The scene is effectively staged from Tinker Bell's point of view and requires Hook to be drawn in an up-shot. Particularly his last pose, which shows him rising up in perspective, puts the viewer at a low eye-level.

This is Hook, the actor, who has no intention of departing the next day.

Drawing from this angle could present a challenge for the animator. Foreshortening Hook's elongated head is not an easy thing to do, but Frank knew that it was necessary to present the character in a high, superior position.

_________________________________

|

| Sleeping Beauty (1959) (Merryweather) (Seq. 7: Fairies Plan (directed by Eric Larson), Sc. 12) (00:11:27–31) |

After Maleficent's curse on the Princess Aurora, the three good fairies try to decide what to do next. Tea and cookies magically appear as the discussion about the evil witch continues. Merryweather suddenly bursts: "I'd like to turn her into a fat ol' hop toad!"

Frank takes full advantage of the scene's acting opportunities. During the first part of the dialogue, Merryweather works herself into a squashed position with shoulders raised and head lowered. This pose serves as a strong anticipation for the jump that follows. For a second it seems Merryweather turns herself into a hop toad. The chubby fairy's body stretches as it shoots upward When completely airborne all her body parts become compressed before landing back on the chair. The fact that a drop of tea leaves her cup on the way down adds a nice touch.

_________________________________

|

| The Sword in the Stone (1963) (Madam Mim) (Seq. 10: Wizards' Duel (directed by Wolfgang Reitherman), Sc. 13.1) (01:04:52–58) |

In this scene, Madam Mim continues to make up the rules about what and what not to turn into for the upcoming wizards duel with Merlin: "[Rule one, no mineral or vegetable]... only animal. Rule two, no make believe things like pink dragons and stuff. Now..."

Mim feels in charge here and is confident she will be the winner of this battle, knowing very well that she is going to cheat. Her theatrical poses display a sense of the fun she is having. When pink dragons come to mind, her hands gesture wildly to emphasize that those would be forbidden creatures to turn into.

Drawing-wise Frank, might have struggled a bit trying to get the head angles and hand positions just right, but as always he succeeds in orchestrating an interesting acting pattern that communicates the character's true feelings. Mim's emotion here is a sort of playful overconfidence.

_________________________________

Frank Thomas catches trout in the High Sierras on his sixteenth birthday in 1928. Some of the characters Thomas brought to life at Disney include Captain Hook in Peter Pan, two squirrels in The Sword in the Stone, and the Queen of Hearts in Alice in Wonderland.

OPPOSITE, Thomas drawing a canine model for 101 Dalmatians in 1961.

This Snow White sequence, animated by Frank Thomas, was a breakthrough in depicting believable emotions.

TOP, infant Franklin with mother Ina and brothers in Santa Monica, 1912;

ABOVE, Frank W. Thomas, Sr., president of Fresno State College, poses in 1919 with sons (left to right) Frank, Jr., Craig, and Lawrence.

Old friends: Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas in the 1980s.

The Flying Mouse contains scenes of sincere emotion and pathos that appealed to Frank Thomas. "If [Disney] is going in that direction," he thought before applying for work at the studio, "there might be something there that would interest me."

Mickey's Elephant (1936), starring Pluto the pup, contains one of Thomas's earliest solo animation performances.

The challenge facing Thomas with scenes of the dwarfs grieving over Snow White's body was to make the animation into "realistic, sincere, believable action."

Pinocchio gives the performance of his life on stage in Stromboli's puppet theatre, exuding the show-off joy of the amateur entertainer. His spontaneity required detailed planning by animator Thomas. The final impression is that the puppet is "making it up as he goes along."

OPPOSITE TOP LEFT, a caricature of hirsute Thomas as Pinocchio's alter ego.

In The Pointer, Thomas animated Mickey encountering a huge bear; attempting to save himself, he touts his celebrity: "Why, I'm Mickey Mouse. You've heard of me, I hope."

The deer in Bambi, developed by Frank Thomas and Milt Kahl, brought a rare compliment from Walt: "Thanks, fellows. Those personalities are pure gold."

BELOW, Thomas feeds a model for Bambi in 1942.

Frank Thomas, sketching in Argentina, was the only animator among the artists, writers, and musicians Walt brought to South America in 1941.

Sergeant Thomas of the Army Air Corps unit visits Lillian and Walt Disney, circa 1944.

A postwar assignment: Ichabod Crane, whose fear of the Headless Horseman progresses from nuanced nervousness to full-blooded panic.

The wicked stepmother in Cinderella was Thomas's first villain, an assignment he found "a terrifying chore."

Thomas continued in the early 1950s to bring life to villains, some quite mad, such as the Queen of Hearts in Alice in Wonderland, and paranoid, such as Captain Hook in Peter Pan.

TOP, Frank, his wife, Jeanette, and daughter, Ann, 1949;

BOTTOM, a Thomas family Christmas card, late 1950s.

Two dogs chewing on spaghetti sounds unromantic, but in Thomas's sensitive hands, the sequence became an icon of romance.

Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas view test animation for the three good fairies in Sleeping Beauty on a Moriola, circa 1958. Thomas's intensity working on this film landed him in the hospital.

OPPOSITE, Frank Thomas (far right) relaxed by playing piano in the Firehouse Five Plus Two, a Dixieland jazz band formed by Ward Kimball (on trombone) in the 1940S;

THIS PAGE, Thomas used his piano perch for people-watching opportunities;

BELOW, entertaining at a 1947 studio function was the Huggajeedy 8, forerunner of the Firehouse Five Plus Two. Thomas is behind Walt Disney (seated right) and Kimball stands at right.

A sequence in The Sword in the Stone of a lovesick girl squirrel and a reluctant human boy transformed by magic into a squirrel features one of Thomas's finest acting performances.

The dancing penguin waiters in Mary Poppins (1964), animated by Thomas and Ollie Johnston, stole the show from Dick Van Dyke.

Frank Thomas, at age 61, working on Robin Hood (1973).

_________________________________

_________________________________

Ollie Johnston always felt that the characters he animated were living beings. "I never thought of them as just lines on paper—to me Pinocchio, Bambi, and Mickey really existed," he stated once.

It is that conviction that led to a very personal approach toward animation, one where the animator analyzes and eventually identifies with the character's emotions. Those feelings become the springboard for what the drawings will look like and how they will move on the screen.

Ollie never considered a particular design style that a film might call for to be a dominant factor in his animation. It was always the core of the character's emotional state he was trying to get to more than anything. That insight was the most important thing that motivated him. "If the animator doesn't understand what the character is feeling, the audience won't either," he said.

Most young animators tend to overlook this important aspect when trying to create believable animation.

The temptation to get started right away and draw before analyzing what is going on in the character's mind is often too great. But those scenes will only show graphic motion, nicely executed perhaps, but void of any real emotional impact on viewers.

Applying Ollie's philosophy can be a game-changer for many animators who are unsure of why their animation isn't "coming off the screen" like classic Disney films do. It might sound simplistic, but when Ollie says: "Don't animate drawings, animate feelings!" there is a profound meaning to those words. The idea is to learn how to draw so well that you don't have to think about the quality of your draftsmanship as much, instead you need to focus on the characters' performance. Animate from the inside out, understand and feel what they go through.

It is often helpful to search among one's own family or circle of friends for inspiration. Do I have an uncle or a cousin who has a similar personality to the character I am animating? What would my uncle do in a situation like this one? Observing people's behavior in real life is a tremendous asset to an animator's work.

After Ollie Johnston arrived at Disney in 1935 he was put to work as an in-betweener, which was common for any newcomer. It was a way for the studio to find out about the young artist's discipline, level of drawing, and work ethics. After in-betweening on several shorts, Ollie caught the eye of animator Fred Moore, who was looking for a new assistant. Production on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was about to begin, and Ollie ended up not only in-betweening Moore's scenes, but also doing clean-up work on the dwarfs before eventually animating a few scenes himself. Ollie was in awe of his mentor's talent; "Fred just couldn't make a drawing that wasn't appealing." He also learned that part of what made a Moore scene look so alive was the fact that strong visual changes were taking place within his characters. The amount of body mass always remained the same but by treating it like a flexible water balloon, new lite was added to otherwise stiff-looking animation.

Ollie took full advantage of this principle when he was given a few scenes featuring various townspeople to animate for the 1938 Mickey short The Brave Little Tailor.

_________________________________

|

| Early work on The Brave Little Tailor. |

_________________________________

Walt Disney saw plenty of promise in Ollie's work, and soon the young animator joined colleagues Frank Thomas and Milt Kahl to help supervise the animation of the character of Pinocchio. While some of the film's story and design issues were being addressed, Ollie did animation for short films like The Pointer, The Practical Pig, and Mickey's Surprise Party.

Fred Moore's influence is evident in these early Johnston scenes.

_________________________________

|

Mickey is on the lookout for a bear; Three naughty wolves cause all kinds of trouble for the little pigs; Ollie's versions of two Disney superstars.

|

_________________________________

Ollie's concept for Pinocchio's personality was that of a well-meaning, naïve little boy:

"All he wanted to do is please his father Geppetto, but his lack of life experiences got him into trouble. After all, he had just been born." The sequence in the film when Pinocchio comes to life was animated by Ollie, but Fred Moore still lent a hand when appeal and drawing needed to be strengthened.

_________________________________

|

| Pinocchio might be made out of wood, but he acts like a real kid; Johnston literally brought Pinocchio to life in his earliest scenes. |

_________________________________

Another section of the film that benefited from the Johnston touch was Pinocchio's conversation with the Blue Fairy in Stromboli's wagon. As Pinocchio tries to make excuses for not going to school, his nose starts to grow, the punishment for lying. The acting is subtle here; Pinocchio goes back and forth from being bewildered by his nose change to still trying to convince the Blue Fairy of his innocence. It is clear to the audience that he is very uncomfortable throughout the scene, because deep inside he knows that not telling the truth is probably a bad thing.

_________________________________

|

| Pinocchio's nose begins to grow. |

_________________________________

While Ollie's teammates Frank Thomas and Milt Kahl moved over to the Bambi unit, he was asked to help supervise the animation of cupids and centaurettes for the Pastoral sequence in Fantasia. These sexy fantasy creatures had been designed by Fred Moore, and Ollie brought them to life with feminine grace. He later recalled enjoying their "makeup" moments, when cupids apply lipstick and rouge to the girls' faces. Originally animated topless, the clean-up artists later added floral covers in order to appease family audiences.

_________________________________

|

| Johnston animated plump cupids and sultry centaurettes in Fantasia's Pastoral Symphony; A makeup moment in the "Pastoral" sequence. Clean-up artists would later add floral covers to the topless centaurettes. |

_________________________________

When story work for Bambi was finalized, Ollie and the other animators went to work and produced some of the most heartwarming and enchanting animated pieces of personality animation ever done. Particularly the motion of the deer characters has an almost poetic quality to it. Because these movements are often synchronized to music, the result looks elegant and balletic. One of those scenes was animated by Ollie. At the beginning of the movie, some time is spent showing how the young faun is still unsteady on his legs, and has difficulties balancing his steps. Bambi has just fallen to the ground yet again, and all the bunnies excitedly encourage him to stand up. With all this encouragement he is determined to show them that he is very much capable of walking. Bambi's back is staged toward camera, we see him placing his weight on his left rear leg, then the right and left again, as his upper body rises up. There is definitely some effort that goes into getting up this way. He then proceeds to walk away from camera, followed by several bunnies. If there is such a thing as "poetry in motion" then this scene is it. Bambi gets into these beautiful poses on specific musical beats. Motion and music perfectly complement each other.

_________________________________

|

| Bambi's early attempt to walk was poetry in motion. |

_________________________________

One of Ollie's most charming scenes featuring Thumper, the rabbit, is when he suggests to Bambi that clover's green leaves are really awful to eat. He knows his mother is watching, so he lowers his voice as he talks into Bambi's ear. In this scene he is telling a secret to a friend in a typical childlike manner. Ollie enjoyed animating this type of sincere and entertaining character moment, unlike the upcoming assignments he would soon receive.

_________________________________

|

| Thumper advises Bambi that clover's green parts "sure is awful stuff to eat!" and tells him a secret. |

_________________________________

The training and propaganda films produced during the war years were not much fun to work on, according to Ollie. But he did enjoy taking on the two leading ladies in the 1943 short Reason and Emotion. These characters live inside the head of a young woman, and they represent opposing sensibilities of her psyche. Their design is a far cry from the realism of Bambi, as these two are cartoony types, with potential for expressive animation. Ollie took full advantage of this assignment and brought the characters to life with a lot of guts. Reason is the conservative type, always proper and well-mannered. On the other hand, Emotion is impulsive and fun-loving, but irrational. The story offered rich situations for these two female opponents to disagree and fight with each other.

_________________________________

|

| Ollie explores staging and contrasting attitudes for the female characters in Reason and Emotion. |

_________________________________

After the end of WWII, Disney got back to theatrical features with the 1946 musical film Make Mine Music. One of the short films included was based on Sergei Prokofiev's composition Peter and the Wolf. For this section, the Disney artists drew character designs that are round and cartoony, yet the way they move displays a great deal of subtlety. You can see in Ollie's animation of Peter and his Grandpa a careful balance of broad movement and delicate acting. When Peter is caught leaving the house in pursuit of the Wolf, Grandpa's hand grabs the kid in a forceful move and carries him back inside. The forest is dangerous; kids have no business going on a hunt.

_________________________________

|

| Johnston finds the right staging for Peter and Grandpa in this layout sketch. |

_________________________________

After Grandpa dozes off, Peter very warily approaches the old man and reclaims his toy gun from under his heavy arms. These movements are handled with believable posing and timing: a real kid trying to outsmart his grandfather.

The film Song of the South gave Ollie plenty of opportunities to act out his characters in the broadest way possible. Dialogue scenes with Brer Bear, Brer Rabbit, and Brer Fox required razor-sharp timing. The key poses needed to read very clearly, because they were usually held for a brief moment, until a new thought process led the character to move into a different direction.

Ollie animated the argument between the fast-talking Fox and the massive Bear over who is going to enjoy Brer Rabbit for dinner.

_________________________________

|

| Brer Rabbit is all shook up by Brer Bear's grip. |

_________________________________

|

| Brer Fox proved Ollie could handle more eccentric animation. |

_________________________________

Having been typecast in the past on adorable-type characters, Ollie proved on Song of the South that he was perfectly capable of zany, eccentric character animation.

The short film Johnny Appleseed from the 1948 feature Melody Time turned out to be a much less enjoyable assignment than the exuberant characters in Song of the South. Ollie recollected years later that Johnny didn't have a strong range of emotions: "He never got mad, never showed any deep feelings about anything." Nevertheless Ollie did beautiful scenes with the character at the beginning of the short film, picking apples while singing a song. His movements are based on realistic actions, but there is a light cartoony touch as well. Whenever Johnny jumps, he stays up in the air for a few frames longer than a real person would, before landing on the ground. This kind of timing adds a bit of elegance as well as fantasy to the scene.

_________________________________

|

| Johnny stays in the air just a beat longer than is realistic, adding elegance to the scene. |

_________________________________

Ollie got the chance to show his talent for comedic timing in the Sleepy Hollow section of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad. The antagonist Brom Bones is furious with jealousy when Katrina starts to flirt with Ichabod. He waits outside her house, ready for a confrontation with the schoolmaster. As Ichabod exits, he saves himself by taking advantage of the double door situation.

_________________________________

|

| Not only does Ollie plays up the comedy in Ichabod's animation, but the much more realistic Brom Bones goes through a hysterical routine as well. |

_________________________________

After producing several features that were comprised of individual short films, Disney returned to full-length feature story telling with Cinderella. The principal human characters like Cinderella, Lady Tremaine, and Prince Charming were handled very realistically, while the King and the Grand Duke turned out to be cartoony types. The stepsisters Drizella and Anastasia fall somewhere in-between. Ollie Johnston enjoyed developing these two comedic villains. They are extremely spoiled by their mother and take every opportunity to make Cinderella's life a daily hell. Their appearance is more on the humorous side; Ollie refrained from drawing them as truly ugly, grotesque types, he preferred to play up their funny antics. One scene, however, was an exception. Toward the end of the film, Lady Tremaine (the stepmother) presents her two daughters to the Duke. After an awkward curtsey, Anastasia remarks: "Your grace." In this close-up scene Ollie tried purposely to portray her as ugly as possible, so that the Duke would react in a repulsed manner. When Walt Disney saw the scene in pencil form, he told Ollie: "You might want to pull that expression back a little, she looks hideous." The corrected scene still shows a very unattractive Anastasia.

_________________________________

|

| Making Anastasia as ugly as possible. |

_________________________________

In 1952 Disney released a charming short film called Susie, the Little Blue Coupe. The story was developed by Bill Peet and it deals with the ups and downs in the life of an automobile. It wasn't the first time Disney turned modes of transportation into successful animated personalities—the train Casey Jr. in Dumbo and the plane Pedro in Saludos Amigos were living, breathing machines. But Susie was the first "thinking" automobile, a true challenge for any animator. Ollie Johnston found clever ways to humanize certain auto parts. The windshield became the eyes, the hood was turned into a nose, and the wheels assume functions of arms and legs. The audience completely identifies with this humanized vehicle, because of the character's sincere emotions. Susie adores her new owner at the start of the film, but she is heartbroken at a later age, when being discarded onto a second-hand lot and eventually to a junkyard. The animator's challenge was to inject human emotions into a machine and make it look entertaining. Ollie animated Susie's body with surprising elasticity even though it is supposed to be made of metal. One of animation's most lovable inanimate objects.

_________________________________

|

| Susie was animation's first "thinking" automobile. |

_________________________________

Working on the title character of the film Alice in Wonderland meant a shift for Ollie Johnston from broad animated types like Susie to a more finessed and realistic style of animation. Live-action reference was filmed to provide a basis for the animators' work. Ollie found this method somewhat restrictive because the main acting choices were made by actress Kathryn Beaumont. But there were scenes that did call for the animator's imagination. Ollie drew Alice meeting the talking doorknob, who encourages her to drink out of a particular bottle in order to change her size. Only then would she be able to pass through the tiny door. Early attempts fail and Alice becomes increasingly frustrated. Emotions like these on a realistic character needed to be carefully drawn and timed. Ollie pointed out years later that animating Alice wasn't one of his favorite assignments, but that he learned a lot from working with live action. "It teaches you about subtlety," he said.

_________________________________

|

| Although Ollie found working with live-action reference challenging, he admitted that he learnt a lot from the experience. |

_________________________________

Ollie also animated the more caricatured King of Hearts, who turned out to be a much easier assignment. Broadly designed as a tiny character and in stark contrast to his mountainous wife, the Queen of Hearts, Ollie gave the King a unique way of running. His feet are not drawn at all, instead the lower end of his coat propels him to move forward. It is a nonsensical, fun type of motion.

_________________________________

|

| The King of Hearts from Alice in Wonderland. |

_________________________________

But it was Ollie's animation of Alice that impressed Walt Disney, so naturally he offered him the part of Wendy in the upcoming production of Peter Pan. Sensing Ollie's frustration, Walt changed his mind and handed him Smee, Captain Hook's pirate sidekick. This character assignment led to one of the funniest, appealing and most interesting cartoon creations ever created. Smee is basically a nice guy who feels the need to act mean only because his boss is the villainous Captain Hook. He even apologizes to Tinker Bell for capturing her so that Hook can interrogate the pixie. Smee often acts uneasy and is intimidated by the Captain. Ollie Johnston animated him with hilarious nervous gestures and attitudes. At one point in the film, Smee offers Hook a shave. Unbeknown to him, he ends up shaving the back side of a seagull instead.

Sheer disbelief and panic overcomes him when he finds Hook's head gone. "I never shaved him this close before!" His hands quiver as he feels through the wet towel searching for the missing scalp. He grabs the top of his hat and shakes it, not knowing what to do next. This is an extremely funny performance, full of inventive and surprising gestures.

_________________________________

|

| Smee is one of Ollie's most entertaining creations. |

_________________________________

Ollie ended up drawing most scenes with Smee, a character who ranks among his best animated efforts. Comic timing and brilliant acting choices make him stand out as a Disney sidekick who works for a villain but comes across as a likable and entertaining type.

The dog characters in Lady and the Tramp required the kind of realistic approach in terms of their movements not seen since Bambi. These canines needed to walk and run with real weight. Lady and the Tramp is a sincere love story, making simple cartoony designs out of place.

Ollie did scenes with most of the dogs, including Tramp and Lady. One of his favorite dogs turned out to be Trusty, the old bloodhound. Ollie sympathized with this warm, grandfatherly type, who had lost his sense of smell. Trusty's very loose skin gave the animators the opportunity to show these folds in overlapping actions, particularly in dialogue scenes. Ollie applied strong squash and stretch to Trusty's face which not only adds age, but it is simply fun to watch.

_________________________________

|

| Trusty, the old bloodhound who has lost his sense of smell. |

_________________________________

For the production of Sleeping Beauty, Walt assigned specific characters to certain animators. For the most part that animator would be responsible for that character only. An exception was the three fairies, who often were portrayed as one unit. Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather stand firm against Maleficent, help raise Aurora in the forest, and the happy ending is largely their work. But their personalities do differ from one another, which made them interesting and fun to work with. Ollie and his colleague Frank Thomas animated all of the fairies' important acting scenes. With all three of them often appearing in the same scene together, staging and composition became an interesting challenge. Clear silhouettes in their poses were very important, so that the group image did not become confusing to an audience. Luckily the widescreen format provided ample space to place these three ladies in.

_________________________________

|

| Flora and Fauna gently encourage Merryweather to give her gift. |

_________________________________

The film One Hundred and One Dalmatians was groundbreaking for its sketchy look and modern art direction, but characters like Pongo and Perdita still needed to be animated the old-fashioned way. The routine of bringing Disney characters to life with drawings on sheets of paper had not changed at all. The animators started out by studying real Dalmatians before caricaturing them for animation.

_________________________________

|

| Ollie observes the anatomy and motion of real Dalmatians; A rough concept sketch for the moment when Pongo faces Cruella De Vil for the first time. |

_________________________________

At the beginning of the film, Ollie animated Pongo's decision to pursue a young lady with her female Dalmatian, who had just passed by the house. He tricks his master Roger Radcliff into believing that it is time for a walk by changing the time on a clock. There is a strong sense of determination to catch up with the two ladies. Pongo pulls Roger along with all his might, until he finally spots them on a park bench.

_________________________________

|

| Pongo straining to catch up with Anita and Perdita. |

_________________________________

A few key scenes involving the character of Nanny in One Hundred and One Dalmatians were also animated by Ollie. Visually she comes across as a possible relative of Sleeping Beauty's three fairies.

_________________________________

|

| Nanny is similar in style to Merryweather from Sleeping Beauty. |

_________________________________

The Sword in the Stone continued the sketchy visual style that was introduced with One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Walt Disney had been critical of this "unfinished looking" approach to his animated films, but most animators enjoyed seeing their own pencil drawings move on the screen (instead of inked tracings). Ollie had a lot to do with developing the relationship of three of the main characters, Merlin, Wart, and Archimedes, the owl. They present an interesting dynamic. Merlin puts it upon himself to give young Wart a real education. Even though he does not succeed very well in this endeavor, the boy is in awe of the wizard. Archimedes is actually the smartest of them all and criticizes Merlin's efforts frequently. Ollie animated most of the opening sequence of the film, when we first see Merlin as he is having trouble getting water out of a well. Eventually Wart appears as he literally falls through the roof of Merlin's house, just in time for tea.

_________________________________

|

| Wart, Merlin, and Archimedes from The Sword in the Stone. |

_________________________________

Even though Ollie enjoyed working on characters like Wart and Merlin, he thought that their relationship never reached the kind of depth you would feel with Mowgli and Baloo from The Jungle Book, the animated feature that followed The Sword in the Stone.

In-between those two pictures, the animators were asked to animate characters that interacted with human actors. In the classic film Mary Poppins, Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke share the screen with cartoon farm animals, racehorses, and four cheerful penguins. Ollie Johnston animated these arctic birds as busy waiters, eager to serve Mary Poppins. The penguins' movements as a group needed to be choreographed carefully, their hectic but enthusiastic actions would otherwise come off as confusing to watch.

_________________________________

|

| The penguin waiters from Mary Poppins. |

_________________________________

The Jungle Book is a unique Disney film, its story was kept extremely simple so that the characters would have plenty of time to interact with each other. Walt Disney knew that the entertainment needed to come from the animal characters' performances, which left the animators with more responsibility than usual. Previous Disney films had been much more story-driven, but The Jungle Book relied completely on strong character animation. The studio at that time had a small but powerful animation unit that could deliver performances of the highest level. For the most part, animators were handed out complete sequences to animate, no matter how many characters were involved. That type of casting resulted in a situation where different animators worked on the same personalities. It gave them the chance to not only develop individual characters, but complex relationships as well.

Ollie Johnston focused on Baloo and Mowgli, and he also animated scenes with Bagheera and the Girl at the end of the movie. Baloo's introduction in the film is one of Ollie's masterpieces. The bear's carefree nature is immediately established by his on-screen singing and "dance walking."

_________________________________

|

| Baloo's dance walk was inspired by a demonstration given by Walk Disney. |

_________________________________

Those moves look completely natural and even improvised, yet a scene like this one requires a lot of analysis and careful planning from the animator. The character's weight shifts constantly, arms and legs have separate unique moving patterns, and the action is synchronized to a musical beat. This complex kind of motion means that all drawings are done by the animator, there are no in-betweens. Every position is unique and important. Ollie recalled that Walt Disney himself had acted out Baloo's steps one day in the hallway of the studio. That little performance by Ollie's boss became the foundation for the personality of the bear.

Ollie Johnston again developed some of the principal characters for the film The Aristocats. For most of his life, Ollie had been a dog-owner, and a lot of research for his canine animated characters was done right at home. But when he started to work on Duchess, the mother cat, and her three little ones, he proved that he had an affinity for felines as well. The kittens Marie, Toulouse, and Berlioz are effectively based on real children. As one would expect, the two brothers gang up on their sister often, and when things go wrong the familiar blaming game ensues. Their personalities come through during a music lesson and when Toulouse paints a portrait of Edgar, the butler. Their behavior and attitudes are sincere and childlike.

_________________________________

|

| Although a dog-owner, The Aristocats proved that Ollie also had an affinity for felines. |

_________________________________

Ollie also animated scenes with Amelia and Abigail Gabble, a couple of English geese who giggle constantly. Watching them on the screen, many in the audience probably remember an aunt or two with similar character traits.

_________________________________

|

| Many in the audience probably remember Amelia and Abigail Gabble, an aunt or two with similar character traits. |

_________________________________

While these geese needed to move in a naturalistic way, Prince John from the film Robin Hood had to act much more human-like—after all, he was an anthropomorphic lion. His sidekick Sir Hiss might slither like a real snake, but he is also able to get into human-like poses by using his tail as a hand. Ollie saw the potential for rich personality material, and he created tour de force performances with these two comedic villains. Their facial expressions are based on the actors who provided their voices. Peter Ustinov is Prince John, a cowardly lion, and Terry-Thomas is Sir Hiss, a sniveling snake. The film's story might not come up to classic Disney standards, but as far as character relationships go, this is one of the most entertaining. Prince John seeks constant confirmation for being a good monarch and when Sir Hiss doesn't comply, physical punishment follows. Nevertheless, Hiss is committed to pleasing his boss, which makes him a partner in crime. It was important that Ollie handled both characters. If another animator had drawn Sir Hiss, for example, their interactions would not have been as seamless. When Prince John acted aggressively, Ollie knew immediately how the snake would have to react.

_________________________________

|

| The insecure Prince John; Ollie captures the uneasy relationship between two comic villains. |

_________________________________

For the film The Rescuers, Ollie was assigned to several characters. He supervised the animation of the orphan girl Penny and Rufus, the old cat. He also developed the personality of Orville, the albatross who runs his own airline. Several important acting scenes featuring the mice Bernard and Bianca were also drawn by Ollie. This is very diverse group of characters, from sentimental and comic to leading types. It is fair to say that Ollie carried a large part of this picture with quality animation, but also quantity. His most important contribution was arguably developing Penny into a character the audience would feel for. This is a girl who is sad for most of the film, not necessarily an appealing attitude to watch for long. But the way Ollie expressed her inner feelings to Rufus reveals that she still holds a glimmer of hope to be adopted one day, and that makes her sympathetic and appealing.

_________________________________

|

| Ollie Johnston put a lot of himself into his role of the orphan Penny and the cat Rufus in The Rescuers. |

_________________________________

Ollie's farewell animation assignment was for the 1981 film The Fox and the Hound. At that time Disney's veteran master animators had taken on a second role as teachers to a new generation of animators. Ollie lectured and gave advice to several newcomers to the studio, including Tim Burton and Glen Keane. But he still found the time to animate one sequence. Tod, the fox meets Vixey in the forest, and his attempts to impress her result in some awkward, but funny moments.

_________________________________

|

| Ollie's final animation assignment was The Fox and the Hound. |

_________________________________

Both Ollie and his colleague Frank Thomas stated that they did not feel challenged working on The Fox and the Hound. The story material and the character concepts were too familiar and reminded them of previous films they had worked on. It was time to put down the pencil and pursue new interests. For the next few years Ollie and Frank wrote a number of important books on character animation and Disney philosophy in general.

Looking over some of Ollie Johnston's drawings, there is a lot to admire. A special appeal can be seen in all of them, whether it is a hero or a villain we are looking at. Ollie never forgot what he had learned from his mentor Fred Moore, that charm is an important ingredient in depicting a character. Without it, the audience might lose interest.

It is also interesting to observe Ollie's light touch with pencil and paper. It seems like he never got frustrated during the animation process. Just a few careful construction lines with delicate pencil strokes on top. This meant that he spent little time on one given drawing, he quickly moved on to the next ones. Ollie Johnston was not only one of Disney's best animators, on many film productions he was also the fastest. What an astounding talent!

_________________________________

|

| Pinocchio (1940) (Pinocchio) (Seq. 4.9: Blue Fairy Frees Pinocchio from Cage (directed by Hamilton Luske), Sc. 21) (00:48:24–27) |

These beautiful drawings define Pinocchio's emotions sensitively and with great insight. The Blue Fairy has reappeared and is wondering why he didn't go to school.

Being locked up in a cage Pinocchio feels embarrassed to face the Fairy. "I was going to school... 'til I met somebody." During the first part of his statement he looks concerned; he doesn't quite know what to tell her. But, the fact that he met somebody is actually the truth, and his expression changes to a smile. For a second he is proud of himself and his explanation, so far so good. But moments later he changes his angle and reports that he ran into two big monsters with big green eyes. Perhaps a little lie will get him out of this interrogation.

Ollie found the perfect uneasy gesture to visualize the dialogue. Pinocchio uses a finger to twirl one side of his shorts. Ollie emphasizes the word met, as Pinocchio leans forward showing a hint of confidence in what he just said.

_________________________________

|

| Alice in Wonderland (1951) (Alice) (Seq. 3: Alice and the Doorknob (directed by Hamilton Luske), Sc. 22) (00:09:04–07) |

Alice has gone through a lot in an effort to try and pass through a miniature door. When she reduces her size hoping she would be able to pass through, the doorknob informs her that he is locked. Ollie animated Alice's frustrated reaction during her encounter with this strange character from Wonderland. In this close-up scene she slides her right hand up her face in an attitude of disappointment and annoyance. During this action Alice's nose is affected by being flattened for a short moment. It is an effective way to show a soft part of her face reacting to the touch of the firm palm of her hand. This gives the illusion that the audience is watching a flesh and blood character on the screen. A subtle contact like this one makes a big difference in making a series of drawings come alive.

_________________________________

|

| Peter Pan (1953) (Mr. Smee) (Seq. 11: Hook Tricks Tinker Bell (directed by Clyde Geronimi), Sc. 6) (00:53:15–19) |

As Captain Hook declares to Tinker Bell that he intends to leave the island, Mr. Smee reacts surprised, but delighted. It was his wish all along to sail away and forget Peter Pan. "I'm glad you agree, Cap'n [hic], I'll tell the crew."

Smee quickly hides the bottle he was enjoying inside the piano and shows his excitement through a clapping gesture. A hilarious little hiccup follows, before he leaves the scene with the intention to inform the ship's crew.

Ollie's acting choices reveal Smee's misunderstanding of the situation, which is right in character.

Judging from the hasty way Smee disposes of the bottle tells us that he feels guilty drinking the wine in the first place. During the mid-sentence hiccup, his startled expression is supported by the stretch of his hat. In anticipation of his exit, Smee takes a couple of steps backward to gain some momentum. This is a beautifully textured and choreographed scene.

_________________________________

|

| Lady and the Tramp (1955) (Trusty) (Seq. 11: Jock and Trusty Propose (directed by Hamilton Luske), Sc. 17) (01:02:35–39) |

After the embarrassing dog pound episode, Trusty and Jock pay a visit to Lady, who is now confined to a doghouse. When Tramp suddenly arrives he is being met with contempt and disregard. It is clear that Lady is not the least interested in seeing him.

Trusty offers support by telling her: "If this pussin is annoying you, Miss Lady..." Followed by Trusty: "...we'll gladly throw the rascal out!"

Trusty's expression is full of disdain as he says the line of dialogue over his shoulder.

Every one of his mouth shapes communicates that emotion very clearly. Since this is an old bloodhound with an extremely soft muzzle configuration, Ollie could take full advantage of this elasticity. Strong squash and stretch is applied here, as well as caricatured mouth shapes. As Trusty turns around, the motion of his long ears supports the head move nicely.

_________________________________

|

| The Jungle Book (1967) (Baloo) (Seq. 4 (directed by Wolfgang Reitherman), Sc. 126) (00:26:46–51) |